Ruins of Gaines' Mill, photographer unknown, c. 1880s.

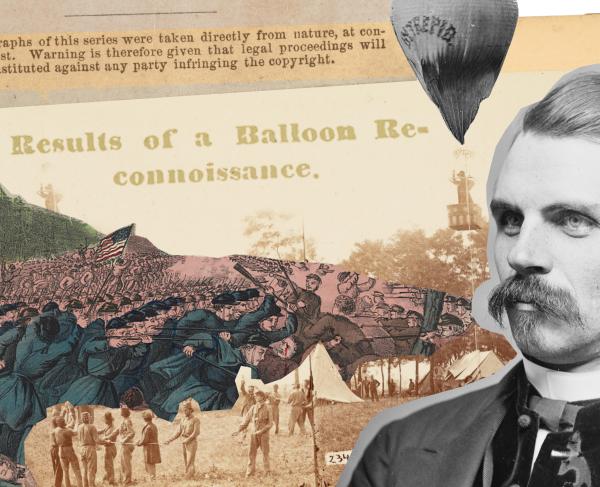

By the spring of 1862, photographers had yet to capture great Civil War documentary images. While Southern photographers had secured the first Civil War photos at Fort Sumter and Northern photographers had recorded numerous camp scenes as well as soldiers on the battlefield of Bull Run, true photojournalism, at least as we know it today, had not been achieved.

The opportunity finally seemed at hand in the spring of 1862 when at least three photographers traveled to Virginia to capture scenes related to what we now call the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles.

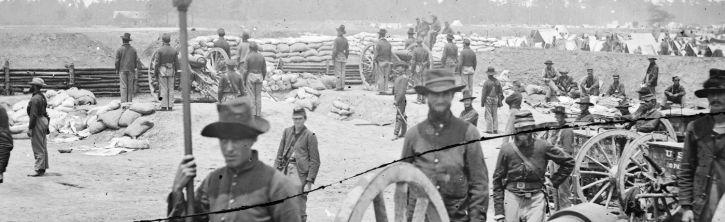

James Gibson was among the more prolific yet obscure Civil War photographers. Gibson arrived in April 1862 and through June captured more than 100 documentary photos including at least sixty at Yorktown, where Union forces besieged the famed colonial town for nearly a month. Views of heavy siege guns and scenes around the enormous Camp Winfield Scott comprised most of Gibson's series yet it is likely that he also recorded portraits for soldiers.

Where Union General George McClellan went, so went Gibson (along with fellow photographer George Barnard, apparently serving as Gibson's assistant) to Cumberland Landing to White House Landing and to within sight of the spires of Richmond. There, Gibson and Barnard exposed numerous plates at the recent battlefield of Fair Oaks, also known as Seven Pines, May 31 - June 1, 1862. Victory, or in the case of Fair Oaks, not being driven away, was a crucial element in the recipe for securing battlefield scenes - if the enemy won, photographers from the losing side lacked access to the scene of conflict. Gibson took photos on both sides of the Chickahominy River recording, among other things, Union balloon operations.

Before Fair Oaks, Vermont photographer George Houghton had arrived on the Peninsula and secured scores of images focused upon Vermont troops and the places they went. Houghton’s photos remain among the most obscure of the Civil War but have been at last presented in a recent book, A Very Fine Appearance.

In the wake of the Battle of Fair Oaks, Gen. Robert E. Lee took command of the Southern forces and within weeks launched an assault upon the Union’s isolated right flank and lines of communication. This resulted in the Seven Days Battles: June 25 - July 1, 1862. From Lee’s first attack at Beaver Dam Creek, McClellan began a steady retreat which for a while precluded post-battle photographs at any of the Seven Days battlefields. Gibson did, however, capture an incredible documentary image of soldiers wounded the day before at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill as well as others at Savage Station — before the fighting there on June 29.

Having no access to battlefield sites after the Union retreat, George Barnard headed eastward and recorded photos at Fort Monroe, Yorktown and with a particular emphasis upon the historic City of Hampton, which had been burned by Confederates, oddly enough. More photographers came to the Peninsula along with Union General Ulysses S. Grant’s movements there in 1864. Cold Harbor, White House Landing and Charles City Court House were among the subjects covered.

In April 1865, photographer John Reekie finally accessed the scene of Lee’s only Seven Days victory—the bloody battlefield of Gaines’ Mill. The costliest battle of the Seven Days also saw a slightly bloodier engagement, Cold Harbor, on nearly the same ground. Reekie took images of the exposed dead at both battlefields.

Although the Battle of Gaines’ Mill was not actually fought at Dr. William Gaines’ mill, it was the most notable landmark in the vicinity and therefore the battle bears its name. Playing on this fame, John Reekie shot a photo of the mill, which had been burned the previous year by Union General Philip Sheridan’s forces. After the war, other photographers captured scenes of the Gaines’ Mill at various stages of reconstruction. By then, the world of documentary photography had changed from practical non-existence to a budding profession with roots on the Virginia Peninsula during the Seven Days Battles.

There are 29 critical acres of battlefield land in Virginia, at Glendale, and at Gaines’ Mill/Cold Harbor that we have the opportunity to save in...

Related Battles

6,800

8,700