"A Deluge of Lead and Iron"

The Mine Run Campaign (November 27 - December 2, 1863) was the final encounter in a cut and thrust conflict between legendary Confederate General Robert E. Lee and Union General George G. Meade in the aftermath of the battle of Gettysburg. After the Union army dramatically repulsed Lee’s advance in Pennsylvania, the Army of Northern Virginia was forced to abandon its invasion of the North. Meade, criticized for failing to follow up on his victory, was considered timid by many in Washington and was under considerable pressure to mount a counter-offensive.

This led to the Bristoe Campaign, a series of skirmishes and small battles fought in Virginia in October and November of 1863. The campaign ended after two Confederate brigades were captured at Rappahannock Station and Lee crossed the Rapidan River in defeat. The Union Army took position on the river’s northern banks and prepared to strike another blow.

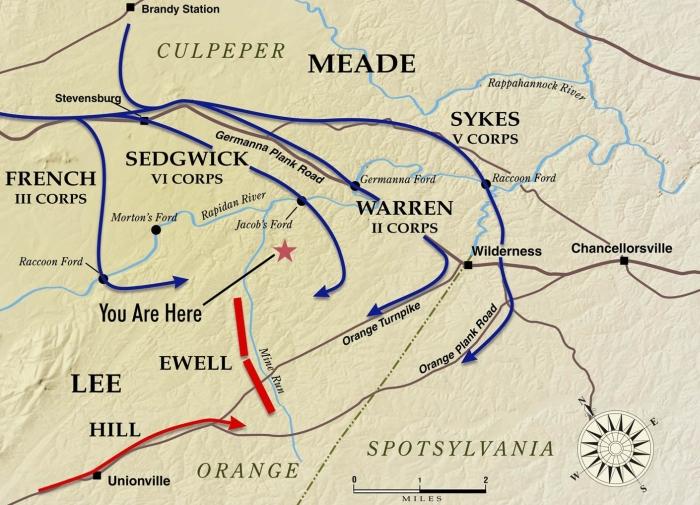

In the days preceding November 26, Meade received detailed information about Lee’s subsequent project: the construction of a fortified defensive position bounded by the Rapidan to the north and Mine Run to the east. Bolstered by the knowledge that Lee was short of men on his right (or eastern) flank, Meade engineered an intricate plan that would allow him to move his 80,000 men across the lower fords of the Rapidan River, advance along the Orange Plank Road behind Mine Run and envelop Lee’s right flank.

If Union forces moved quickly enough, they would be able to engage Lee from the flank and rear and Union forces would be concentrated while Lee would only have part of his army to meet the attack. The plan was well constructed, but intricate and complicated. Lee was a shrewd commander and in order to exploit the gap in his defenses, Meade’s army needed to smoothly execute a complicated river crossing and a rapid advance.

Meade originally planned to launch his assault on November 24 but was delayed by heavy rain, which muddied the roads and made them difficult to traverse. During the delay, Lee accurately surmised that the Union Army was about to move and prepared his men for action.

Finally, on November 26, the Federals advanced. A number of issues immediately slowed their march: mud and rain retarded troop movements, some divisions departed hours after they were ordered to and others were soon lost in the Virginia woods. Artillery that was slated to cross the Rapidan at Jacob’s Ford had to be transferred to a different crossing due to steep banks and an inadequate bridge. This created a traffic jam which ensnared thousands of Union soldiers. Meanwhile, Lee took a more aggressive role than Meade had anticipated, leaving his fortifications and using them as a base from which to organize an active defense. Maj. Gens. Jubal A. Early and Edward Johnson were dispatched to counter the Union advance. The armies were on a collision course.

Fighting erupted at about 11 a.m. as Union Brig. Gen. David Gregg and his horsemen forded the Rapidan and approached New Hope Church, three miles to the south of the main body of Union infantry. Gregg, who had a reputation for tardiness, was already several hours behind his targeted time and soon after fording the river met resistance from Confederate cavalry under the command of Maj. Gen. J.E.B Stuart. Gregg advanced slowly and fighting raged at the Church until about 2:30 p.m. when Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s infantry arrived and captured the strategic high ground to the west of the Church. Soon, however, Union Maj. Gen. George Sykes arrived to reinforce Gregg with his Fifth Corps, repulsing Heth and gaining the high ground, where the Union remained for the rest of the day.

Earlier, Union Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren had led the main thrust of the Union infantry advance to the north, leading his Second Corps across the Rapidan and positioning his men along the high ground at Locust Grove. Warren was new to corps command and is best remembered by historians for identifying and defending Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg. Meanwhile, Jubal Early and his Confederate forces arrived and skirmished with Warren’s line at Locust Grove, but found it too well fortified to launch a full-scale assault.

Union Maj. Gen. William French and his Third Corps were supposed to meet Warren at Locust Grove. French had departed late and was a key player in bungling the main elements of Meade’s plan—speed and surprise. Early’s advance, too, had effectively ended the possibility of slipping around Lee’s flank.

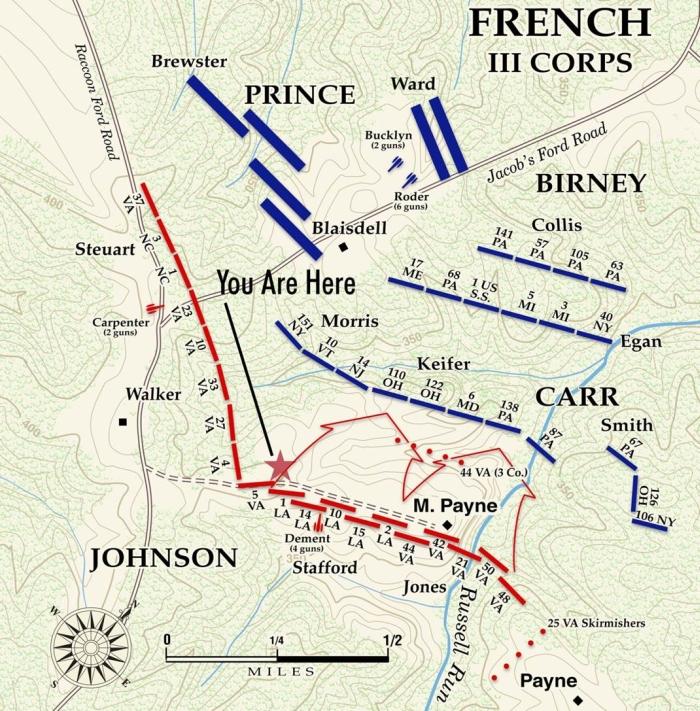

When his forces finally crossed the Rapidan, General French came upon Brig. Gen. Henry Prince. Prince was the lead element of French’s Corps, and had come to a fork in the road two hours earlier. Fearing an engagement with Confederate forces, Prince had dispatched scouts to examine the roads and had taken no subsequent action. It was later noted that either road would have led to their destination. Before French could come to a decision about which road to take, the skirmishers Prince had dispatched engaged the rear elements of a Confederate force.

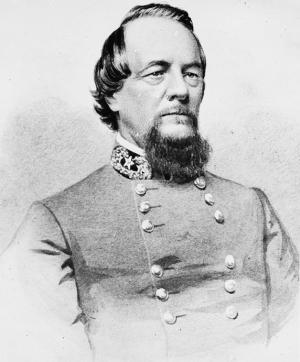

Prince’s scouts had uncovered Maj. Gen. Edward “Old Clubby” Johnson’s division. Johnson earned this nickname (one of many) from his habit of carrying a large club as a walking stick, in and out of battle. After the rear elements of his division were fired upon, Johnson countermarched his lead units to the scene and aggressively counterattacked. French in turn ordered Prince’s entire division into battle, initiating the largest and deadliest engagement of the Mine Run Campaign—the Battle of Payne’s Farm.

It is unlikely that Johnson knew he would soon be facing three times his number, but it did not seem to matter to him. His 5,300-man division assumed the offensive against an entire Union corps with another corps in support—altogether nearly 32,000 potential foes. Ultimately, some 20,000 soldiers on both sides fought back and forth through dense woods and farmland owned by a man named Madison Payne. Johnson’s veterans proved their merit and Prince’s line nearly buckled before General Joseph Carr’s three brigades—part of which were as of yet untried in battle—advanced to and stabilized the Union left flank. One man of the 10th Vermont described the fight as “a deluge of lead and iron that swept over us. The musketry was not in the least of a jerky or intermittent sort, but one continuous roll.”

Johnson would not let up. When his lead brigades returned he tried without success to envelop the Union line. The battle climaxed in one of Payne’s open fields with ever-arriving Union reinforcements blunting uncoordinated Confederate attacks.

Among the Confederate forces was 19-year old Pvt. Alexander Tedford Barclay of the Stonewall Brigade, who, at the height of the battle, advanced into the clearing bearing the regimental colors, and planted the flag well in advance of his line. According to one Union account, “Thousands of shots were fired at that lone hero. ‘Shoot the man with the flag’ was heard all around. Hearing a sergeant near me give that command, I said: ‘Don’t shoot that man, he is too brave to kill.’” Barclay, who had enlisted in the 4th Virginia in 1861 and fought in all of its battles, made it back to his line unscathed.

After hours of intense fighting, the Union had suffered 900 casualties to the Confederates’ 540. Only as darkness fell did the battle peter off and the Union advance halt, a mile short of its objective point. Soldiers on both sides—those who had fought at Antietam, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg and elsewhere— remembered it as one of the most violent and heated actions of the war. Col. Charles T. Collis of the 114th Pennsylvania judged it: “one of the sharpest and best fought affairs of the war. The musketry was the most terrific any of us had ever heard, and the chances of getting off without a decent wound was about as poor as it possibly could have been.” Confederate Alexander Pendleton stated that the battle was: “as warm a musketry fire as I have experienced for a good while – certainly worse than I have been in since Sharpsburg.”

Under the cover of darkness, Lee and Meade examined their exhausted forces. Both had suffered heavy casualties, and many of their regiments were running short of ammunition and food. The temperature rapidly dropped as the sun set—water froze and frost began to form. Pickets had to be relieved every half hour to keep them from freezing, but no fires were permitted for fear of disclosing the position and strength of the soldiers. Lee eventually ordered his army back to the previously fortified high ground, in some cases forced to abandon Confederate wounded and dead.

On November 28, Meade found the Confederates located on dominant ridges, with defenses designed by experienced hands to concentrate overlapping angles of fire on any approach. Lee hoped that Meade would attack him, reenacting the mistakes Union General Ambrose Burnside had made eleven months earlier at Fredericksburg, and began to plan his own counter attack.

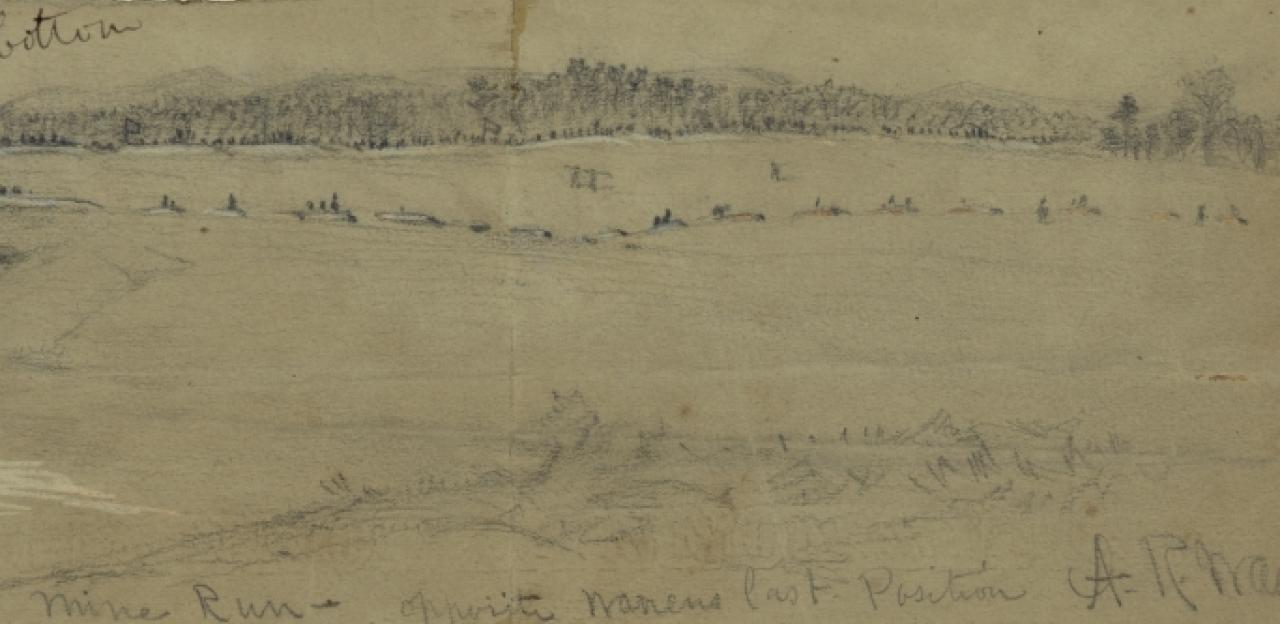

Meade dispatched Warren’s Second Corps to engage Lee’s right flank beyond Mine Run, but by the time Warren arrived in position, the sun had again begun to set. Union forces spent another miserable night in subzero weather, without shelter or fire. The water in their canteens froze, and soldiers from both sides were forced to move constantly to avoid frostbite.

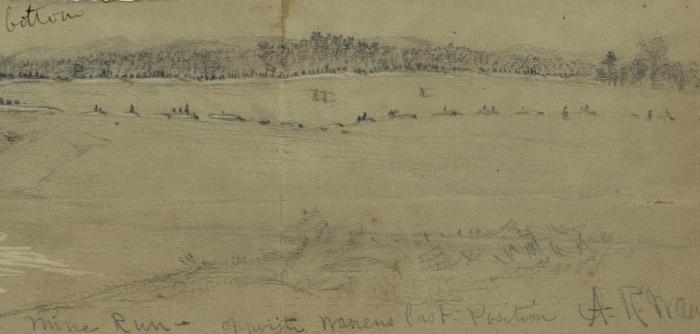

Union troops under Warren’s command spent the night dreading the next day’s advance; veterans knew that to attack entrenched cannons and muskets along a hill was all but suicidal, and they could hear Confederate soldiers entrenching. Few expected to survive, and the next morning 28,000 men arranged themselves in silence, preparing themselves to storm the hill. After Warren observed the Confederate position in the pale morning light, he deemed an assault impossible and summoned Meade to make an inspection of his own.

Rather than order what probably would have been a hopeless assault, Meade withdrew his forces back across the Rapidan. Fredericksburg had not been forgotten. Edward Basset, a twenty-one year old farmer enlisted in the first Minnesota Volunteer regiment, who had been at Fredericksburg, later wrote: “Thus we got out of another bad spot. I believe that if we had charged, as first ordered, not ten men of our Regt. would have come out alive. It was one of the worst places that I have ever seen. We were lucky. I shall never forget Nov. 30th 1863."

Meade was frustrated with himself and furious with French, whose bumbling he believed had inhibited the Army of the Potomac from utilizing its numerical advantage. Lee too was discouraged. He felt that in waiting for a Union attack, he had missed the chance for a decisive victory, remarking: “I am too old to command this army. We should never have permitted those people to get away.”

The Mine Run Campaign marked the end of the war in the east for 1863—both armies went into winter quarters after the guns fell silent. In total, Lee had taken 680 casualties to Meade’s 1,272, and the engagement proved indecisive. Both armies were dispirited: Meade blamed French, Sykes, and Prince for not displaying enough determination and speed in executing his plan and Lee was forced to confront the arduous prospect of another long winter running short of supplies, men, and morale.

The Mine Run Campaign clearly displayed many crucial elements of the war in late 1863. Robert E. Lee, forced to revert to the same cat and mouse game he had previously engaged in on Southern territory, again proved himself to be a wily and capable general. At the same time, however, Lee can be seen taking a more active role in battlefield command, leaving less to his lieutenants, as irreplaceable losses in the officer corps threatened to detooth the Army of Northern Virginia. Nevertheless, the actions of Jubal Early and especially Edward Johnson demonstrated that the Southern fighters retained an independent-minded bellicosity that would continue to stymie their generally more cautious Union counterparts.

The conduct of the Union Army is likewise indicative of its own strong points and shortcomings. George Meade, while still beleaguered by Washington critics, had driven Lee’s army more than 120 miles in five months and had achieved significant victories at Gettysburg and Bristoe Station. His men liked him a good deal more than did Washington, and he further reinforced their respect with his decision to call off the final attack at Mine Run. The failure of the Mine Run Campaign can in many ways be ascribed to persistent problems in the lower echelons of Union leadership: lack of initiative, timidity, and poor staff work. At Mine Run, these factors prevented the rapid advances and all-or-nothing attacks that it usually takes to destroy an army in the field. These problems would continue to hamper the Army of the Potomac for the rest of the war.

If General Meade had launched the attack planned for November 30, the name of Mine Run would be inscribed prominently and violently in Civil War history. Without the bloodshed of a major assault, however, the campaign is often overlooked as a small occurrence between the larger set-pieces of Gettysburg and the Wilderness. This perspective does not do justice to the intensity of the fighting at Payne’s Farm, which veterans pointed to as one of the toughest battles, big or small, of the war, and does not do justice to the nature of 19th century warfare, in which planning and maneuver are just as important to achieving results as are large-scale battles. After the Union victory at Gettysburg, it was far from inevitable that 1863 would close with Lee’s army pinned down deep in Southern territory. Achieving this advantageous position along the Rapidan required months of blood and toil from the Army of the Potomac, and it set the stage for the campaigns that would finally end the war in the east.

Related Battles

1,272

680