The Crater

The Battle of The Crater

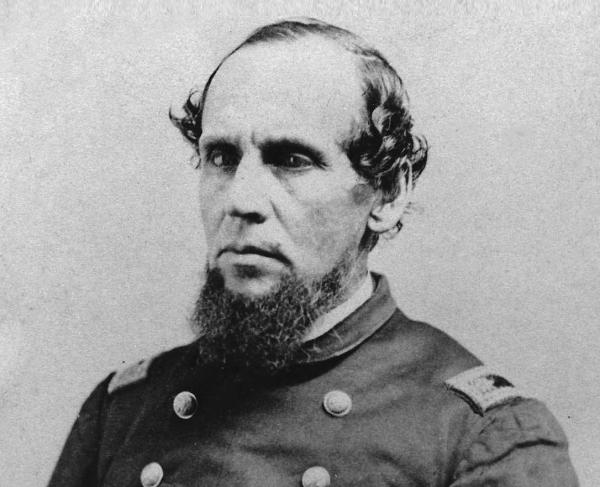

Colonel Henry Pleasants of the 48th Pennsylvania, a mining engineer by profession, saw a way to end the stalemate at Petersburg. Pleasants proposed to build a mine with a large gallery under Elliott’s Salient on the high ground in the Confederate line, pack the gallery with black powder, and blow a huge hole in the enemy line, opening a clear path to Petersburg. Despite skepticism, apathy, and outright opposition from Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, Pleasants began digging on June 25, completing a 510-foot shaft within three weeks. By July 27, the mine was packed with 8,000 pounds of gunpowder and ready to ignite.

Initially, the Union high command placed little stock in the mine’s potential. But by the end of July, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had decided to authorize the explosion and use it to capture Petersburg in a spectacular coup de main. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s plan was to pass his leading division through the gap created by the explosion and then have his troops turn north and south respectively to widen the breach, and clear the way to the vital Jerusalem Plank Road. The Ninth Corps commander chose Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero’s division of black troops to spearhead the assault. Though these troops had spent most of their service guarding wagon trains and building fortifications, Burnside believed their enthusiasm would compensate for their lack of combat experience. What’s more, each brigade in Ferrero’s division trained for its role in Burnside’s carefully choreographed scheme.

On the day before the assault, however, General Meade ordered Burnside to select a white unit instead. Burnside had his division commanders draw lots for the job. Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie—possibly the worst general officer in the Union army—picked the short straw. Untrained, ill-prepared, and led by a drunken coward, Ledlie’s men would lead one of the Civil War’s most calamitous attacks the next morning.

The mine exploded at 4:44 a.m. on July 30, 1864. The result stunned everyone who witnessed it. "Clods of earth weighing at least a ton, and cannon, and human forms, and gun-carriages, and small arms were all distinctly seen shooting upward in that fountain of horror," remembered a newspaper correspondent. When the dust settled, a crater 130 feet long, 60 feet wide, and 30 feet deep scarred the landscape where Elliott’s Salient had stood a moment before. A total of 352 Confederates were killed by the blast.

Ledlie’s men struggled to scale their own trenches, then staggered forward into a scene of indescribable confusion and horror. Paralyzed by contradictory orders and a lack of leadership, the Federals failed to either widen the breach or rush toward the high ground at Blandford Church, the attack’s ultimate target. Instead, many Yankee soldiers plunged into the Crater or froze in positions on either side of it. Reinforcements merely added to the lack of command and control.

But Union incompetence is only part of the story. The Confederate defenders on either side of the Crater recovered quickly after their initial shock and poured fire from both flanks into Burnside’s men. Well-placed artillery raked the ground on all sides of the Crater. An indecipherable labyrinth of trenches, bombproofs, and covered ways also served to freeze the attackers in place.

Shortly after he learned of the explosion, Gen. Robert E. Lee called for fresh troops to regain the lost ground. The only available reinforcements belonged to Maj. Gen. William Mahone’s division, posted two-and-a-half miles west of the Crater. Mahone selected two of his five brigades—a Georgia unit and his own Virginia Brigade, which included many men from Petersburg—to make the march. Utilizing stream beds, back roads, and covered ways to avoid detection, Mahone reached the scene at about 8:30 a.m.

The Virginians were the first to charge, their zeal for combat sharpened by the presence of United States Colored Troops. The black soldiers, among the last of Burnside’s men to occupy the Crater, had shouted "No Quarter" during their attack, and Mahone’s men prepared to fight on that basis.

Charging across the open ground in a compact formation with bayonets fixed, the Virginians reached the edge of the Crater, where they unleashed a deadly volley. The combat became hand-to-hand and men died in heaps, human gore running in streams to the bottom of the horrid pit. The black troops suffered disproportionately as they became special targets for the Confederates. Many were killed after they had surrendered. The Virginians managed to recapture most of the line north of the Crater. The Georgia brigade attacked next, but they made scant progress against the remaining Union defenders.

By then Mahone had summoned to the battlefield a third brigade of Alabama troops under Brig. Gen. John C. C. Sanders. At 1:30 p.m. some 630 Confederates dashed across this field to finish the job the Virginians had started. Many of the remaining Federals now retreated, but others fought, died, or were captured. When the firing stopped, some 3,800 Federals were casualties. The Confederates lost fewer than 1,200 men, including those killed by the explosion.