Cowpens

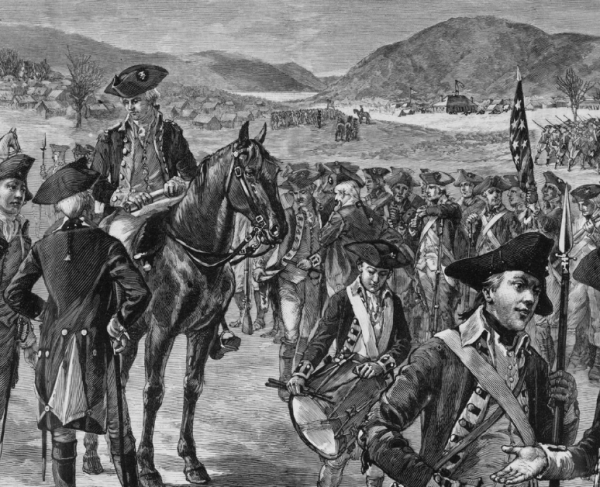

A stunning example of military prowess and skilled leadership, the Battle of Cowpens near Chesnee, South Carolina was a critical American victory in the Revolutionary War. After a string of bad luck in the Southern Campaign since the 1778 capture of Savannah, the American army demonstrated their worth in the Battle of Cowpens on the morning of January 17, 1781, a swift struggle that decisively hindered British forces in the South.

The Battle of Cowpens was a key battle in the Southern Campaign. As a way to defeat the Americans in body and spirit, the Southern Campaign was an initial success for Britain. British troops gained easy victories in conventional battles early in the campaign over an ill-equipped American force. However, by freeing Southern planters’ greatest source of labor and income—slaves—the British did not find many sympathetic allies to their cause in the South. With little loyalist support, the British army faced more challenges in battle as the Southern campaign waged on.

After the American loses at Camden (August 16, 1780), British Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, boosted by these other victories, aggressively pursued American General Daniel Morgan’s forces through South Carolina. Confident that his 1,150 men would continue to be successful in the South, Tarleton chased Morgan’s men without full knowledge of how many men Morgan actually had at his side. Morgan had the upper hand in this regard. Knowing the strength and location of his enemy, Morgan readied his 1,065 men for battle.

On the morning of January 17th, Morgan’s men met the British on wide-open South Carolina pastureland. Kept clear by cattle grazing for most the year, this almost park-like setting allowed for Morgan’s swift military maneuvering. The rolling hills on this sprawling field also served Morgan in deceiving Tarleton that he could secure an easy victory. That was not the case. The night before, Morgan had emboldened his men, quickly establishing confidence that they would defeat the British and on January 17th, Morgan’s words of victory inspired the reality of it.

Morgan knew his men and he knew Tarleton’s. Hoping to hinder any thought of retreat in his men, Morgan positioned his forces between the Broad and Pacolet rivers, ensuring that meeting the British was the only physical option for the Americans. Morgan knew that these men could panic in the early stages of combat, as they had in the American fiasco at Camden in 1780. Boosting morale in his men and safeguarding this confidence with two rivers, Morgan had a chance against Tarleton’s more disciplined and trained troops. Betting that Tarleton would employ typical British field battle tactics by lining up his men in a linear assault, Morgan deliberately left his flanks open inviting Tarleton’s troops to take the bait.

On a small hill in the center of his line elements, Morgan placed Continental Troops from Maryland and Delaware, and made his defense three separate lines: the first of skirmishers; the second with militia and the third and last line consisting of the better-trained Continental Army units. Morgan ordered some trained men to be in first two of three lines and to shoot British officers first so that by the time British got through the lines, the Royal Army would be leaderless and disorganized. As the British advanced Morgan ordered his militia in the second line to fire two volleys and then immediately retire to the rear of the line to be reorganized and fight in reserve behind the line of Continentals and alongside the horsemen who had also been posted there. The maneuver would give the appearance of Americans fleeing, while at the same time concealing the third line which would have the high ground and be able to fire into the British as they assaulted the hill. The arrangement worked. The British took heavy casualties in the initial attack to clear out the skirmishers and take on the militia. By the time they reached the third American line, the British attack fell into disorganized chaos.

Depleted of officers, Tarleton’s men continued to try and press their advantage. An hour into the fighting, elements of Morgan’s Virginia Regiments fired point blank into the British as they attempted a feeble flanking move on the right. Just at the point the British assault was blunted the Americans fixed bayonets and plunged into their enemy. In the melee that followed, Americans seized the two small field pieces the British had brought along for artillery support. The British line crumbled with Regulars throwing down their arms and surrendering.

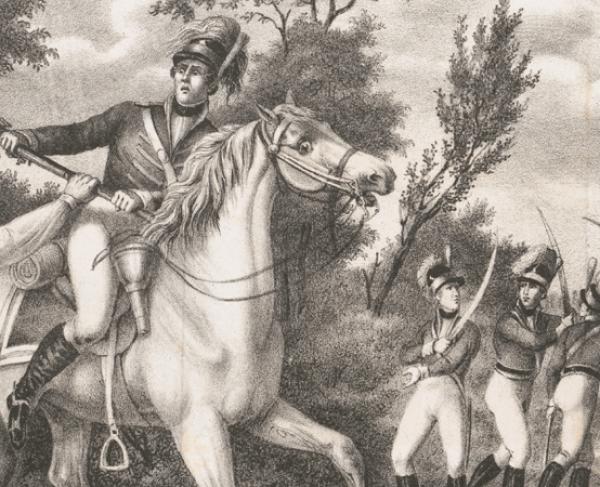

American cavalry then moved forward from behind the third line in an enveloping move to cut off the British. The shock of the sudden movements by the Americans devastated those British who were still left standing. Morgan ordered 100 cavalrymen under William Washington (second cousin, first-removed to George Washington) to meet Tarleton’s men at the third line. Washington’s horsemen attacked on the right and reformed militia from first two lines struck left, overwhelming Tarleton's frazzled troops. Those British who could, tried to flee—only to be hotly pursued by the American cavalry. Washington personally took on Tarleton with his sabre, shouting insults as he attacked. Tarleton shot Washington’s horse out underneath him and like his men fled the field. By 8:00am the battle was over.

Reflecting on this battle, Morgan later bragged, “It was a devil of a whipping!” This defeat further weakened British attempts to wrest the southern colonies from American control and demoralized the large Loyalist population who had counted on the British to maintain a stiff defense against the American cause and those who fought for it.

Related Battles

149

868