Closing the Back Door

Jeffrey D. Wert, Hallowed Ground Magazine

THE RECKONING WAS LONG OVERDUE. SINCE THE CIVIL WAR'S INITIAL WEEKS, THE Shenandoah Valley of Virginia had stood as a lance pointed at the Union's heart: Washington, D.C. In 1862, Confederate General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's campaign in the region had redirected the conflict's course in Virginia. A year later, Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had followed the Valley's roads across the Potomac River and into Pennsylvania. If there were to be a resolution to the war in the Old Dominion, it would have to include the Shenandoah Valley.

As the nation's struggle entered its fourth spring in 1864, operations in the Valley began as a minor phase of overall Union strategy. General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant's offensive plans in Virginia involved a three-pronged movement. While Major General George G. Meade and the Army of the Potomac engaged Lee's veterans, a force under Major General Benjamin E Butler would land on Bermuda Hundred, between Richmond and Petersburg, and move against either or both cities. The final effort would be beyond the Blue Ridge, where Major General Franz Sigel would advance south, up the Valley. In Grant's thinking, the primary campaign was Meade's army against Lee's.

Sigel met with defeat at New Market on May 15. Major General David Hunter replaced Sigel and, with a larger force, penetrated deeper into the Valley. By mid-June, Hunter's troops threatened Lynchburg. Faced with the capture of the railroad center, Lee sent Lieutenant General Jubal A. Early and the Second Corps of the army to confront Hunter. After a month of fearful carnage in the Overland Campaign and with the campaign stalled on the Peninsula at Cold Harbor, Lee committed one-fourth of his infantry and two battalions of artillery to the Valley. His decision — a risky move — affected operations in Virginia for the next four months.

Racing west, Early's troops — they had been Jackson's "foot cavalry" — secured Lynchburg and chased Hunter's men into the Allegheny Mountains. With the Valley cleared of Federals, Early marched north, crossing the Potomac into Maryland. On July 9, the Rebels defeated a Union force at Monocacy before reaching the defenses of the Union capital. Early tested the strongly held works and then withdrew into the Valley. On July 24, Early attacked part of the Union pursuit force, routing the Yankees in the Second Battle of Kernstown. Less than a week later, Confederate cavalrymen rode into Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. When town officials could not pay a tribute, the Southerners ignited fires, which burned more than four hundred residences, businesses, and public buildings.

Early's raid and the Chambersburg conflagration stunned Northerners. It was "the old story over again," editorialized the New York Times. "The backdoor, by way of the Shenandoah Valley, has been left invitingly open." In Washington, meanwhile, Abraham Lincoln saw the prospects for his reelection waning. In his estimation, something had to be done about the "back door" of the Valley.

Lincoln traveled to Fort Monroe, where he met with Grant on July 31. Grant had paid scant attention to the Valley operations until recently. Both men agreed that Union efforts in the region demanded a consolidation of four departments into one military division and a force of sufficient strength to close the back door and to defeat the enemy. At the meeting, however, Lincoln and Grant could not agree on a commander for the soon-to-be designated Army of the Shenandoah. Grant had initially proposed Meade for the command, but Lincoln rejected the idea. Returning to the capital, Lincoln received word from Grant the next day that he had chosen Major General Philip H. Sheridan for the command.

When Grant had assumed the post of general-in-chief, he brought Sheridan from the west to lead the cavalry corps of Meade's army. The 33-year-old Sheridan— a man who possessed energy, intensity, and self-confidence — had commanded an infantry division at Missionary Ridge in Tennessee and had impressed Grant with his aggressiveness. Grant originally brought Sheridan east to instill his combative spirit in Meade's mounted units — and now he tapped Sheridan's belligerence to direct operations in the Valley.

There was not much to Sheridan physically. A short man, about five feet, three inches, with a thick body, he looked like a sawed-off oak stump set upon wooden pegs. A New Yorker described him as "the little man who rode so large a horse." A joke soon circulated in the army that the general had to shinny up his sword to mount his horse. To his men, he was "Little Phil."

Sheridan arrived at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, on August 6, after conferring with Grant outside of Washington. Grant's orders to Sheridan read in part: "In pushing up the Shenandoah Valley, as it is expected you will have to go, first or last, it is desirable that nothing should be left to invite the enemy to return. Take all provisions, forage, and stock wanted for the use of your command; such as cannot be consumed, destroy ... Bear in mind the object is to drive the enemy south, and to do this you want to keep him always in sight. Be guided in your course by the course he takes."

The army that gathered with Sheridan at Harpers Ferry consisted of the veteran Sixth Corps of the Army of the Potomac, two divisions of the Nineteenth Corps transferred from Louisiana, and two infantry divisions and a cavalry division of the Army of West Virginia. Within weeks, Grant sent the First and Third Cavalry divisions from Meade's army at Petersburg to Sheridan. The Army of the Shenandoah and the garrison at Harper's Ferry amounted to upwards of 50,000 officers and men.

South of the Yankees, in camps around Bunker Hill, sat the roughly 13,000 to 14,000 Confederates of the Army of the Valley. Despite the disparity in numbers between them and the enemy, these Southerners were some of the finest combat infantrymen and artillerymen left in their beleaguered nation. Conversely, their comrades in the cavalry units were poorly equipped, armed, and mounted. In a region conducive to cavalry operations, the Rebels faced a daunting foe.

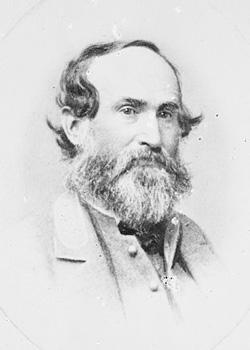

Jubal Early, or "Old Jube" to his men, commanded the Confederates. A redoubtable fighter, Early had more than fulfilled Lee's expectations since assuming command of the Second Corps in May — and Lee's expectations had been high. When he detached Early's troops and approved of the raid into Maryland, Lee tried to retrieve the strategic or operational initiative that he had lost to Grant. To Lee, success in the Valley might lessen the pressure Union forces could bring to bear in the siege at Petersburg and offer the Southerners battlefield victories that could affect the presidential election in the North. The Shenandoah Valley assumed once more a strategic significance.

It was then with August's heat that the final reckoning began. The Yankees marched south on August 10, with the Rebels withdrawing to Fisher's Hill. Before this formidable defensive position, Sheridan halted his army along Cedar Creek. When Sheridan had passed through Washington en route to his command, he had been counseled to act cautiously and to avoid a defeat, which could adversely affect Lincoln's reelection. In Petersburg, meanwhile, Lee ordered infantry and a cavalry division to bolster Early's numbers in the Valley. Lee had decided to risk even more on a victory in the region.

When these Confederates entered the Valley, Sheridan retired northward, halting at Halltown, outside Harpers Ferry. During the retreat, Union cavalrymen began destroying crops and barns, a harbinger of the night of fire and smoke that would descend upon the Valley folk. Early followed the Federals, and operations stalemated for weeks. Sheridan shifted his army south to the Berryville area, with Opequon Creek dividing the opponents. A Union officer described the campaign during these weeks as "mimic war."

On September 2, Union general William T. Sherman wired Washington, "Atlanta is ours, and fairly won." The capture of the city reinvigorated Lincoln's reelection campaign and heralded a change in the Valley campaign. Two weeks later, Grant traveled to the region and met with Sheridan at Charlestown, West Virginia. The general-in-chief had come to order an offensive against Early's army. Before Grant arrived, Sheridan had learned from Rebecca Wright, a loyal Quaker schoolteacher in Winchester, that Major General Joseph Kershaw's infantry division had started back toward Petersburg. With this intelligence, Sheridan presented his own plans for an offensive. Grant approved it, saying: "Go in." Sheridan designated September 19 for the advance.

The Yankees marched before daylight on September 19, with cavalry leading the army across Opequon Creek. Before the Federals stood Major General Stephen Dodson Ramseur's Confederate infantry division. Two days earlier, Early had led two of his divisions to Martinsburg, only to countermarch them when he learned of Grant's visit to the region. Now, however, his army faced piecemeal destruction if he could not regroup his scattered commands before Sheridan swept aside Ramseur's troops. The preceding weeks of relative inactivity had convinced Early that Sheridan lacked aggressiveness. It was a critical misjudgment.

The Third Battle of Winchester began soon after daylight as Ramseur's veterans fought stubbornly against Union cavalry and then infantry, gaining precious hours for Early to bring his other units on to the field east of town. Fortunately for the Rebels, Sheridan funneled his infantry through two-mile-long Berryville Canyon, which resulted in a jammed roadway and delays. It was not until 11:40 a.m. that the Nineteenth and Sixth Corps rolled forward in an assault. Initially, the Federals pushed back the gray-coated defenders, but as the Yankees advanced, a gap opened between the two corps. The Confederate brigades of Major General Robert E. Rodes counterattacked, driving into the gap. Rodes was killed by a piece of an artillery shell, but his veterans stopped the attackers and sent them rearward. Union Brigadier General David A. Russell's division met Rodes's and Major General John B. Gordon's Rebels, and the combat raged for thirty minutes in what a soldier called "a stand-up fight."

The musketry burned the ground, leveling men. A Georgian described the effects of one volley, "It was so terrible that it really looked sickening." A Yankee claimed that the Rebels "fought more like redskins, or like hunters, than we." Russell fell mortally wounded, but his troops sealed the breach, repulsing Rodes's and Gordon's Confederates.

A lull ensued, lasting for more than two hours. Brigadier General George Crook brought up his two divisions of the Army of West Virginia and bolstered the Union lines. In turn, Crook shifted one division across Red Bud Run to turn the Confederates' left flank. (Crook formed his ranks on the ground secured by CWPT.) In his report, Sheridan claimed that the turning movement had been his idea, but the evidence indicates that it had been Crook's. Sheridan's assertion and other claims caused a postwar rift between the two former West Point roommates.

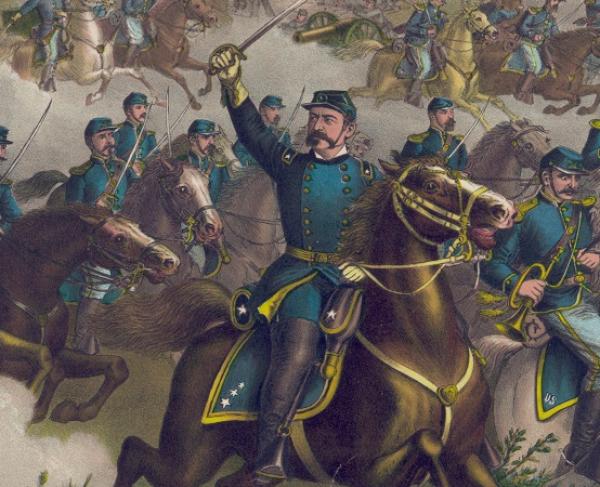

Mid-afternoon, Crook's two divisions aligned one north and one south of the run. To their right along the Valley Pike, Sheridan's cavalry, after pushing their foe rearward during the morning, aligned ranks for a mounted charge. Crook's men stepped out followed by the Sixth Corps and then the mounted units. A whirlwind of Union troops engulfed Early's Rebels. The Southerners fought valiantly, but Federal numbers prevailed, overwhelming the Confederates' inverted L-shaped line east and north of Winchester. Sheridan rode among the infantry, shouting, "to give 'em hell" and to "Kill Every Son of a Bitch."

Early's left flank collapsed first, under the onslaught of Union cavalry and Crook's infantry. Some Confederate units waged stubborn rearguard actions, but they could not stay the rout. In the words of one of Sheridan's staff officers, the Yankees had sent the enemy "whirling through Winchester." Union casualties amounted to slightly more than 5,000 killed, wounded, and missing, while Confederate losses totaled between 1,900 and 2,000. No previous engagement in the Valley had been as bloody.

The Confederates retreated south during the night, halting on Fisher's Hill. Described as "the bugbear of the valley," Fisher's Hill consisted of a series of ridges wedged between Massanutten and Little North mountains. A month before, Sheridan had refused to assail the formidable position, but the victory at Winchester had changed operations. Now, too, Early had too few men to man the works securely. He compounded his numerical weakness by placing his cavalry units in the low ground at the base of Little North Mountain on his left or western flank.

The Federal attack came late on the afternoon of September 22. George Crook had proposed another flank attack against the Rebels. Leading his troops on to Little North Mountain, Crook struck Early's left flank. Rebel cavalry scattered, and the Yankees rolled off the mountainside, smashing into Southern infantry units. To the front, the Union Sixth Corps charged up the face of Fisher's Hill. The attackers, in the words of one of them, poured over the works "in a confused delirious mass."

The defenders fled in a rout worse than at Winchester. In one rearguard action, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander S. "Sandie" Pendleton, who was Early's chief of staff as he had been Stonewall Jackson's, fell mortally wounded. This campaign was killing the soul of Old Jack's Second Corps. The Southerners lost probably 1,000 men, and the Northerners sustained fewer than 500 casualties. As a Rebel soldier, sang, "Old Jube Early's about played out."

The victory at Fisher's Hill opened the upper valley to the Federals. While Early retreated to the gaps of the Blue Ridge, Sheridan marched his army to the Harrisonburg- Staunton area. Here the Yankees remained for nearly two weeks, gathering up livestock and foodstuffs and burning barns and mills. From Petersburg, Grant prodded Sheridan to cross the Blue Ridge and to advance to Gordonsville and perhaps on Richmond. Grant saw the strategic opportunity, but Sheridan disagreed, citing a number of reasons against such a movement.

The Union retrograde march began on October 6, accompanied by a pall of flames and smoke. For three days, Federal cavalrymen torched farms, houses, crops, and mills. The destruction was systematic and organized, unlike anything before in the war. A Pennsylvanian wrote, "the blackened face of the country from Port Republic to the neighborhood of Fisher's Hill bore frightful testimony to fire and sword." Another Yankee exclaimed, "The Valley is all ablaze in our rear." The local residents called it simply, "The Burning." By one estimate the damages exceeded three million dollars.

Confederate cavalry pursued the Northerners, striking at the enemy horsemen. Angered by the Southerners' forays, Sheridan ordered his mounted units to attack the pursuers. On October 9, the Yankees routed the Rebels at Tom's Brook, chasing them for nearly twenty miles in what became known as the "Woodstock Races." Finally, the Federal army halted along Cedar Creek south of Middletown. Sheridan departed for Washington, D.C. to discuss future movements with his superiors. In the camps along Cedar Creek, it seemed that the universal view was the Rebels were "disposed of."

From the south, however, Early's troops were coming. Lee had ordered Joseph Kershaw's infantry division back to the Valley and prodded Early to attack the enemy, whom Lee thought was not as numerically strong as Early had stated. To his subordinate, Lee wrote: "I have weakened myself very much to strengthen you. It was done with the expectation of enabling you to gain such success that you could return the troops if not rejoin me yourself."

On October 17, Early sent John Gordon and a few officers up Massanutten Mountain to examine the Union position along Cedar Creek. The next morning the senior generals met, and Gordon proposed a night march by the Second Corps around the exposed Federal left flank, followed by a daylight assault by the entire army. The officers approved Gordon's plan, and Early issued the orders. It was a brilliantly conceived gamble, unparalleled in the war.

The Second Corps filed off of Fisher's Hill at 8 p.m. on October 18. The officers and men forded the North Fork of the Shenandoah River and on to the Massanutten. Following a "pig's path," they reached the mountain's northern end, waded across the river again at Bowman's Ford, and angled north, halting to align into battle ranks. They were on time, a remarkable achievement. Along Cedar Creek, Kershaw's four brigades waited at Bowman's Mill.

A dense, cold autumn fog enveloped the fields and woodlots around Middletown on the morning of October 19. Minutes after daylight, the Rebels advanced. Kershaw's veterans, emerging from the fog, overran Colonel Joseph Thoburn's Union position on a hill above Cedar Creek, scattering the Yankees. Wheeling northwestward, the Southerners charged toward the Valley Pike. On their right, Gordon's three divisions struck the Federal campsites east of the pike. The Rebel yell echoed through the fog. Beyond the roadbed, men of the Nineteenth Corps reversed their trenches as regiments of the corps were sent forward to slow the assault. Men in these units sacrificed themselves but could not stem the Southern tide.

A soldier called combat a "hell carnival." On this morning, amid a blanket of fog, it was time for the demons in men. The Yankees held for a while, and then were engulfed, fleeing west past Belle Grove, army headquarters, and across Meadow Brook. Beyond the small stream, the Union Sixth Corps shifted to face the assault. Hundreds of Southerners, tempted by the abandoned enemy camps, left the ranks temporarily to get food and discarded items.

Nevertheless, the Confederates drove across Meadow Brook, shoving the Sixth Corps northward in fierce fighting. Brigadier General George W Getty placed his Sixth Corps division in the town cemetery west of Middletown. Getty's men withstood enemy charges. At this point, Early rode into the action and sent his final division, Brigadier General Gabriel C. Wharton's, against Getty's troops. It was a critical mistake, as Early should have directed Wharton's brigades north, down the pike, to outflank any new Union line. Instead, Federal cavalry reached the pike north of town, securing the vital avenue of advance.

With their line outflanked, Getty's men joined in the retreat. Their stalwart defense had saved many of their comrades from capture. The Federals regrouped about a mile north of the village, where Sheridan joined them. He had returned to Winchester from the capital the day before and spent the night there. When he arrived on the battlefield after a storied ride from Winchester, Sheridan was told that units were organized to cover a retreat. "Retreat — Hell!" shot back Sheridan, "We'll be back in our camps tonight."

In Middletown, meanwhile, Early and his officers reorganized their ranks. The Confederates had won a stunning victory, capturing 1,300 prisoners and twenty cannons. About 1 p.m. Early ordered three divisions forward in a reconnaissance-in-force. When the advance disclosed that the Northerners had rallied, Early should have withdrawn the infantry back to the army's position on the north edge of town. Instead, he left them where they had halted, with both flanks exposed and beyond immediate support. The Confederates soon paid dearly for Early's misjudgment.

At 4 p.m., as Sheridan had vowed, the Yankees came. Once more, the Southerners resisted stubbornly, until Union cavalry struck their left flank and Federal infantry lanced through a gap in the line. "Regiment after regiment, brigade after brigade, in rapid succession was crushed," asserted Gordon, "and, like hard clods of day under a pelting rain, the superb commands crumbled to pieces." While rallying some men, Stephen Ramseur, who had just learned of the birth of a child, toppled from the saddle with a mortal wound, dying in Belle Grove the next day.

Sheridan urged his men to "put a twist on 'em," and the Federals swept Early's army from the field. Union cavalry pursued, bagging prisoners, cannon, and wagons. The victory was as complete as the morning's defeat. In all, nearly 9,000 men were killed, wounded, or captured on both sides at Cedar Creek. A Union veteran argued that of . all the battles that he had been in, Cedar Creek "beats them all."

And, so, the reckoning had ended. In a span of a month, Sheridan and his army had won four battlefield victories and had inflicted destruction upon a large swath of the Shenandoah Valley. Early and his outnumbered command had fought with their usual valor, but critical mistakes doomed them against such a formidable opponent. Sheridan emerged from the campaign as a Union hero, and his army achievement helped ensure Lincoln's reelection. No longer did the ghost of Stonewall Jackson haunt the Yankees in the Shenandoah Valley. The back door had been closed.

Jeffry D. Wert is a retired high school high school teacher and the author of seven books, including From Winchester To Cedar Creek: The Shenandoah Campaign of 1864. His forthcoming book, The Sword Of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac, will be published in the spring of 2005.

Related Battles

5,764

3,060

5,020

3,610