Civil War Prison Camps

Gary Flavion

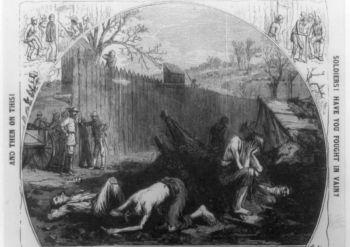

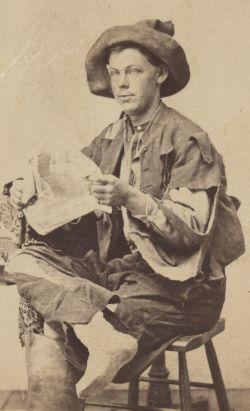

Robert H. Kellog was 20 years old when he walked through the gates of Andersonville prison. He and his comrades had been captured during a bloody battle at Plymouth, North Carolina. In the depths of Georgia, they discovered that their hardships were far from over: "As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror…before us were forms that had once been active and erect—stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin…Many of our men exclaimed with earnestness, 'Can this be hell?'"

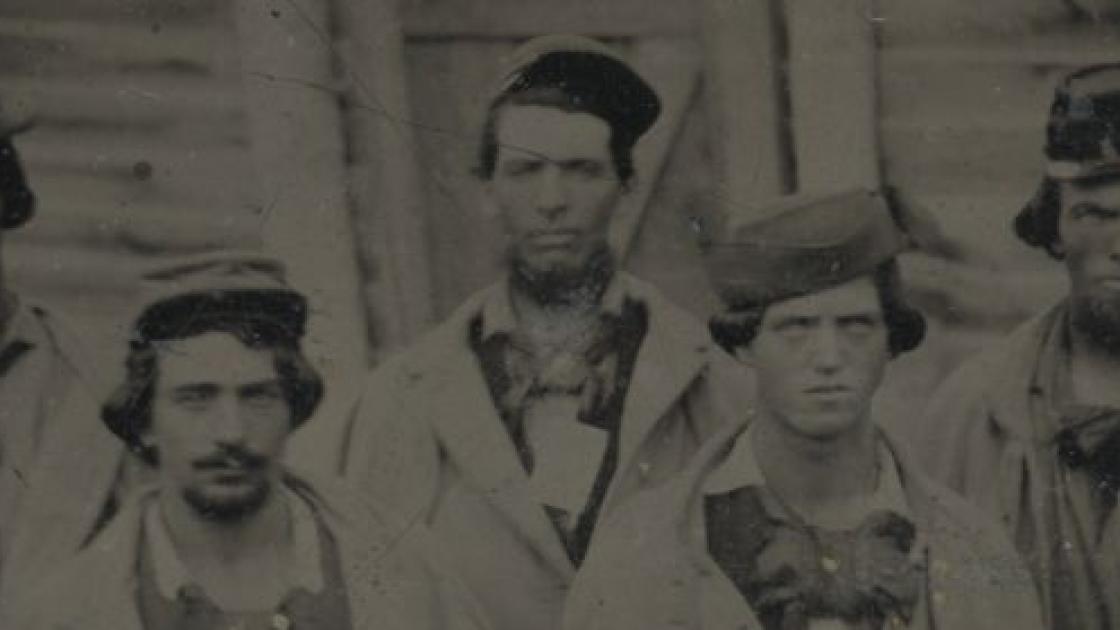

Hardened veterans, scarcely strangers to the sting of battle, nevertheless found themselves ill-prepared for the horror and despondency awaiting them inside Civil War prison camps. While they often wrote frankly of the carnage wrought by bullets smashing limbs and grapeshot tearing ragged holes through advancing lines, many soldiers described their prisoner of war experiences as a more heinous undertaking altogether.

Not every experience behind camp walls was the same, however. Some soldiers fared better in terms of shelter, clothing, rations, and overall treatment by their captors. Others suffered from harsh living conditions, severely cramped living quarters, outbreaks of disease, and sadistic treatment from guards and commandants.

When prisoner exchanges were suspended in 1864, prison camps grew larger and more numerous. Overcrowding brutalized camp conditions in many ways. Of the more than 150 prisons established during the war, the following eight examples illustrate the challenges facing the roughly 400,000 men who had been imprisoned by war's end.

Salisbury Prison (North Carolina)

The Confederacy opened Salisbury Prison, converted from a robustly constructed cotton mill, in 1861. In the early months of the camp's existence, the conditions inside Salisbury were quite good, relatively speaking.

The 120 or so Union soldiers interned there were fed meager yet adequate rations, sanitation was passable, shielding from the elements was provided, and the prisoners were even allowed to play recreational games such as baseball.

However, as the war progressed, the conditions at Salisbury plummeted. By October of 1864, the number of Union prisoners inside Salisbury swelled to more than 5,000 men, and within a few more months that number skyrocketed to more than 10,000.

With the increase in men came overcrowding, decreased sanitation, shortages of food, and thus the proliferation of disease, filth, starvation, and death. This is a common thread among camps over the course of the Civil War.

Salisbury marks a prime example of the effects that overcrowding had on prison populations, especially given the stark contrast in its camp death rate. In 1861, while the population was quite low, the death rate hovered around 2%. In 1865, when the number of prisoners ballooned to its peak, the death rate exceeded 28%.

Alton Federal Prison (Illinois)

Alton Federal Prison, originally a civilian criminal prison, also exhibited the same sort of horrifying conditions brought on by overcrowding. Even though antebellum prison buildings provided some protection from the elements, blistering summers and brutal winters weakened the immune systems of the already malnourished and shabbily clothed Rebel prisoners.

Communicable diseases such as smallpox and rubella swept through Alton Prison like wild fire, killing hundreds. One smallpox outbreak claimed the lives over 300 men during the winter of 1862 alone. Of the 11,764 Confederates who entered Alton Federal Prison, no fewer than 1,500 perished as result of various diseases and aliments.

Point Lookout (Maryland)

Originally constructed to hold political prisoners accused of assisting the Confederacy, Point Lookout was expanded upon and used to hold Confederate soldiers from 1863 onward. Due to its proximity to the Eastern Theater, the camp quickly became dramatically overcrowded.

In September 1863, Rebel prisoners totaled 4,000 men. By December of that year, more than 9,000 were imprisoned. At its peak, over 20,000 Confederate soldiers occupied Point Lookout at any given time, more than double its intended occupancy.

By the time the Civil War ended, more 52,000 prisoners had passed through Point Lookout, with upwards of 4,000 succumbing to various illnesses brought on by overcrowding, bad sanitation, exposure, and soiled water.

Human error in the form of overcrowding the camps –a frequent cause of widespread disease – is to blame for many of the deaths at Point Lookout, Alton, and Salisbury. In some instances, however, simple error and ignorance devolved into treachery and malicious intent, culminating in tragic losses of human life.

Elmira Prison (New York)

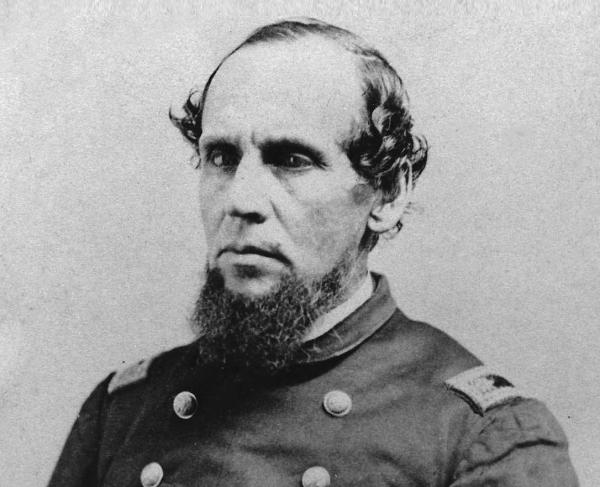

Elmira Prison, also known as "Hellmira," opened in July of 1864. It quickly became infamous for its staggering death rate and unfathoomable living conditions due to the Commissary General of Prisoners, Col. William Hoffman.

Col. Hoffman forced Confederate prisoners to sleep outside in the open while furnishing them with little to no shelter. Prisoners relied upon their own ingenuity for constructing drafty and largely inadequate shelters consisting of sticks, blankets, and logs. As a result, the Rebels spent their winters shivering in biting cold and their summers in sweltering, pathogen-laden heat.

Overcrowding was yet again a major problem. Although Union leadership mandated a ceiling of 4,000 prisoners at Elmira, within a month of its opening that numbered had swelled to 12,123 men. By the time the last prisoners were sent home in September of 1865, close to 3,000 men had perished. With a death rate approaching 25%, Elmira was one of the deadliest Union-operated POW camps of the entire war.

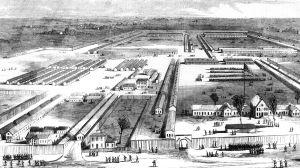

Camp Douglas (Illinois)

A similar disregard for human life developed at Camp Douglas, also known as the “Andersonville of the North." Camp Douglas originally served as a training facility for Illinois regiments, but was later converted to a prison camp. 18,000 Confederates were incarcerated there by the end of the war.

Upon inspecting the camp, the U.S Sanitary Commission reported that the “…the amount of standing water, of unpoliced grounds, of foul sinks, of general disorder, of soil reeking with miasmic accretions, of rotten bones and emptying of camp kettles.....was enough to drive a sanitarian mad." The barracks were so filthy and infested that the commission claimed, “nothing but fire can cleanse them."

Union camp leadership was largely to blame for the death toll. Commandants purposely cut ration sizes and quality for personal profit, leading to illness, scurvy, and starvation.

One prisoner in seven died, for a total of 4,200 deaths by 1865.

Belle Isle (Virginia)

Situated on a 54-acre island within the James River, a stone's throw away from the Confederate capital of Richmond, Belle Isle received the ire of Northern politicians and poets alike.

Lucius Eugene Chittenden, U.S. Treasurer during the Lincoln Administration, described the dreadful and horrifying conditions Union soldiers found at Belle Isle:

"In a semi-state of nudity...laboring under such diseases as chronic diarrhea, scurvy, frost bites, general debility, caused by starvation, neglect and exposure, many of them had partially lost their reason, forgetting even the date of their capture, and everything connected with their antecedent history. They resemble, in many respects, patients laboring under cretinism. They were filthy in the extreme, covered in vermin...nearly all were extremely emaciated; so much so that they had to be cared for even like infants."

Belle Isle operated from 1862 to 1865. In that time, the number of men packing onto the tiny island grew to more than 30,000 men.

The poet Walt Whitman was driven to comment on the shocking living arrangements at Belle Isle after encountering surviving prisoners, appalled at "the measureless torments of the...helpless young men, with all their humiliations, hunger, cold, filth, despair, hope utterly given out, and the more and more frequent mental imbecility."

No wooden structures were furnished for the prisoners at Belle Isle. If they were lucky, several men could be crammed into thin canvas tents, but most were forced to construct their own drafty shelters. The lack of substantial and adequate shelter compounded the prisoners' plight on Belle Isle and increased the amount of death and suffering brought on by disease and exposure.

Modern estimates place the total deaths close to 1,000 men, however, period assessments varied greatly. Despite the controversial number – Confederates claiming only a few hundred and the Union claiming upwards of 15,000 mortalities – the dreadful conditions Federal prisoners faced is unquestionable.

Florence Stockade (South Carolina)

After Atlanta fell to Union forces in September 1864, Confederates forces scrabbled to scatter the 30,000 Union soldiers imprisoned at Andersonville Prison in Macon County, Georgia. Fearing that Union forces could cause a jailbreak at Andersonville, a new Union POW camp was established in Florence, South Carolina. Florence Stockade operated from September 1864 to February 1865 and 15,000 to 18,000 Union soldiers were processed through the camp. Most prisoners had already been imprisoned in Andersonville. Because of this previous imprisonment, they were weaker and more susceptible to the harsh conditions and communicable diseases that flourished at Florence Stockade.

After the war, numerous Union soldiers noted the poor, hastily prepared shelters in the camp, the lack of food, and the high death rate. Imprisoned in both Andersonville and Florence, Private John McElroy noted in his book “Andersonville: a Story of Rebel Military Prisons” that “I think also that all who experienced confinement in the two places are united in pronouncing Florence to be, on the whole, much the worse place and more fatal to life.” In October 1864, 20 to 30 prisoners died per day. By the end of the war, 1 in 3 men imprisoned at Florence died.

Andersonville/Camp Sumter (Georgia)

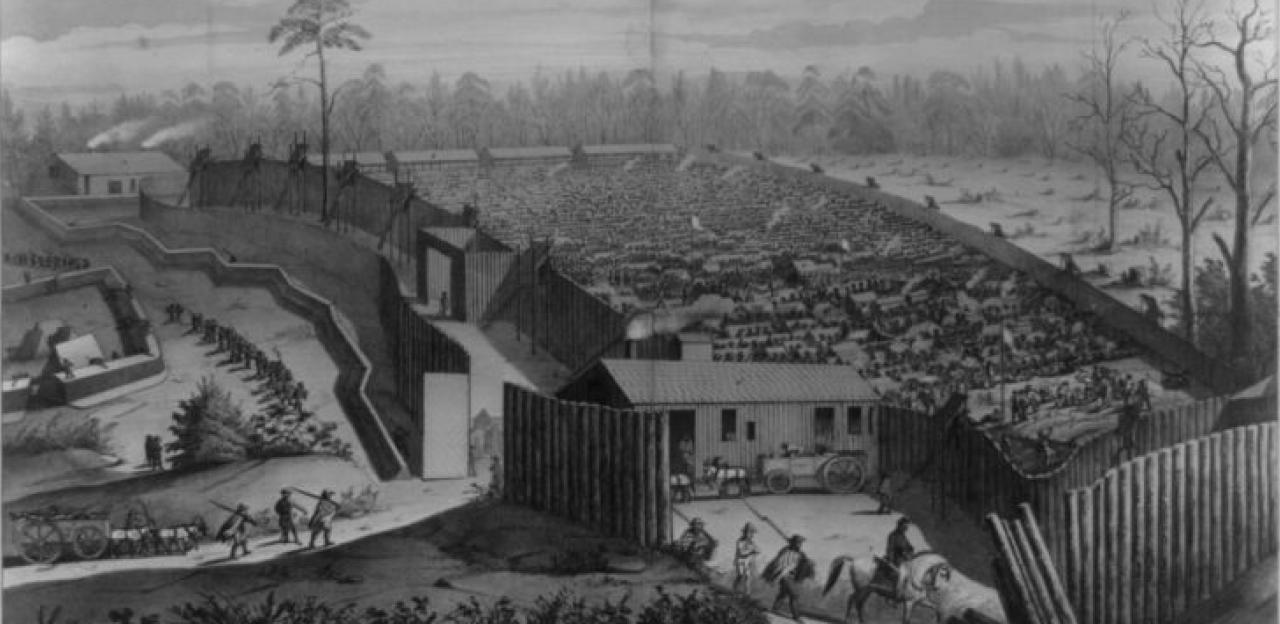

In the 14 months of its existence, 45,000 prisoners were received at Andersonville prison, and of these nearly 13,000 died.

Captain Henry Wirz, commandant at Andersonville, was executed as a war criminal for not providing adequate supplies and shelter for the prisoners. However, modern interpretation of the evidence suggests did in fact face real supply shortages. There were simply too many prisoners and not enough food, clothing, medicine, or tents to go around.

Limited rations, consisting of cornmeal, beef and/or bacon, resulted in extreme Vitamin-C deficiencies which often times led to deadly cases of scurvy. In addition to the high frequency of scurvy, many prisoners endured intense bouts of dysentery which further weakened their frail bodies.

Prisoners at Andersonville also made matters worse for themselves by relieving themselves where they gathered their drinking water, resulting in widespread outbreaks of disease, and by forming into gangs for the purpose of beating or murdering weaker men for food, supplies, and booty.

One prisoner commenting on the daily death toll and foul conditions proclaimed, “… (I) walk around camp every morning looking for acquaintances, the sick, &c. (I) can see a dozen most any morning laying around dead. A great many are terribly afflicted with diarrhea, and scurvy begins to take hold of some”.

The nature of the deaths and the reasons for them are a continuing source of controversy. While some historians contend that the deaths were chiefly the result of deliberate action/inaction on the part of Captain Wirz, others posit that they were the result of disease promoted by severe overcrowding. Andersonville was more than eight times over-capacity at its peak. The shortage of food in the Confederate States, and the refusal of Union authorities to reinstate the prisoner exchange, are also cited as contributing factors.

Despite the controversy, there can be little doubt that Andersonville was the Civil War's most infamous and deadly prison camp. However, the issues raised by Andersonville were shared by many camps on both sides.

Prison camps during the Civil War were potentially more dangerous and more terrifying than the battles themselves. A soldier who survived his ordeal in a camp often bore deep psychological scars and physical maladies that may or may not have healed in time. 56,000 men died in prison camps over the course of the war, accounting for roughly 10% of the war's total death toll and exceeding American combat losses in World War I, Korea, and Vietnam.