Book: The Long Road to Antietam

The American Battlefield Trust had the opportunity to speak with author Richard Slotkin about his book, The Long Road to Antietam: How the Civil War Became a Revolution. This book looks at not only the military aspects of the 1862 Maryland Campaign, but also the complex political challenges and strategic choices facing both the Lincoln and Davis administrations in September 1862.

Civil War Trust: You’ve written a number of excellent books on the Civil War. What attracted you to the 1862 Maryland Campaign as a subject?

Richard Slotkin: The Civil War was really the “Second American Revolution,” as James McPherson has called it, and the Maryland campaign was the crisis of that revolution. The Union victory in that campaign enabled Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which turned the war into what Lincoln called a “remorseless revolutionary struggle.” The war’s transformations of American society were certainly radical enough to justify the use of that term. I think we tend to discount the revolutionary character of that period, because we know what did not happen: the abolition of slavery did not make the US a multi-racial democracy, the Union was not destroyed, constitutional government was not replaced by despotism.

But leaders of North and South had to respond to the crisis with no assurance that the war would not end in the destruction of constitutional government in either or both of the rival sections. Civil wars had always been fatal to republics in the past, from ancient Athens down to the French republics of 1789 and 1848.

To see the crisis from their perspective, we have to understand that Lincoln and Davis were not simply the presidents of stable national governments. They were leaders of embattled political movements, whose regimes were vulnerable to the play of uncontrollable social and political forces. Secession was a revolutionary act, which fractured the order of constitutional government, and made the most radical political actions seem plausible. Both presidents would have to deal with the threat of new secessions by disaffected state governments, and the threat of popular uprisings. Events would pressure Lincoln and Davis to stretch their constitutional authority to or beyond the breaking point, to intensify the scope of combat operations beyond all precedent, to inflict loss and suffering on civilian populations as an instrument of policy. Both would also be faced with demands that they cede their powers, in whole or in part, to a military “dictatorship.” Davis would actually come to that in 1865, by which time it hardly mattered.

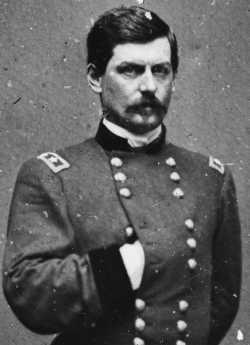

The threat of military dictatorship was far more menacing to Abraham Lincoln, and it was strongest during the crisis summer of 1862. The threat came from General George McClellan: commander of the Union’s largest army, in charge of defending Washington itself; the general Lincoln had to entrust with the conduct of the Antietam campaign.

You place great emphasis on Lincoln’s conflict with McClellan. Why was this so dangerous, and how did it affect the campaign?

RS: During the first year and more of fighting, McClellan was widely regarded as the Union’s best general, even by many of those who faulted him for his slow and hyper-cautious approach to operations. He was unquestionably a superb organizer of troops.

What made McClellan dangerous were his political commitments and his personality, which combined grandiosity with something like paranoia. He was nicknamed “the Young Napoleon,” and in 1862 that was a specific reminder of very recent events: the Second French Republic, established by the 1848 revolution, had been overthrown by Napoleon III in 1852. That same fate had overtaken every historical republic that had fallen into civil war, from Athens and Rome, to Cromwell’s England and Robespierre’s France.

Although he presented himself as a pure-minded professional, McClellan was in fact a partisan Democrat who wanted to preserve slavery as a guarantee of white supremacy. By virtue of his position he became the most powerful Democrat in Washington, the symbolic leader of the opposition party. He also believed he had a divinely appointed mission to save the Republic from what he saw as the twin menaces of Secession and Radical Republicanism. So he fought a two-front war, fending off the Confederates in front and using every resource of politics and public relations to unseat his enemies in Lincoln’s cabinet. Worst of all, McClellan dismissed Lincoln as “the original Gorilla,” a well-meaning but weak-minded “baboon” surrounded by fools and traitors; refused to inform the President of his plans and deliberately flouted or balked at following presidential orders.

He continually reverted to the idea of a military dictatorship, which might come to him through Congressional action, the abdication of his opponents in Lincoln’s cabinet – or even a military coup. Although that last was an extreme idea, he liked to entertain it. He took pleasure in telling his wife, “I have commenced receiving letters from the North urging me to march on Washington & assume the Govt!!” In August, 1862, a few weeks before Lincoln reappointed him to command of the Army of the Potomac, he mused: “If I succeed in my coup everything will be changed in this country so far as we are concerned & my enemies will be at my feet. It may go hard with some of them in that event, for I look upon them as the enemies of the country & of the human race...”

Lincoln’s conflict with McClellan was far more dangerous to constitutional government than the later clash between President Truman and General MacArthur during the Korean War. The Lincoln-McClellan conflict occurred in the midst of civil war and revolution, when the authority of constitutional government itself was under challenge. Like Napoleon, McClellan had created a cult of personality in the Army of the Potomac; and his army was not half a world away, but was entrusted with defense of the president, his government, and the capital of the nation. Even a failed or abortive coup attempt by a few disgruntled officers would have done severe, perhaps irreparable harm to the Union cause, and set a dangerous precedent for the future of constitutional government.

The 1862 Maryland Campaign was a watershed moment within the Civil War. How did Union and Confederate strategies change in this period?

RS: For the first year, leaders on both sides planned for a short war. Each believed that the people on the other side were not deeply committed to their cause, and could be convinced to negotiate a settlement after a few heavy defeats and some experience of the economic costs of war. To make negotiation palatable, each adopted a program of political “conciliation.” Davis offered to guarantee the Union’s western states free passage of the Mississippi River and access to New Orleans, through which most of their produce was traded to the world. Lincoln offered guarantees that slavery would not be threatened in the states where it already existed.

By July 1, 1862, both Presidents realized that they had underestimated their opponents’ political commitment and military strength. To achieve their aims – independence for the South, or a restored Union – each would have to wage a more vigorous and destructive war, attack the fundamental structures of the enemy’s society and break its people’s will to resist.

Davis would seize the military opportunity opened by the stalling of the Union’s offense in the west, and Lee’s defeat of McClellan in the Seven Days' Battles (June 25-July 1), to authorize a grand counteroffensive – simultaneous advances by all three of his major field armies. One force would invade Kentucky and try to recover central Tennessee; Lee’s army would threaten Washington and invade Maryland. These military moves were coupled with a political offensive. The commanders of the invading armies would reach out to the leaders and citizens of Kentucky and Maryland, inviting them to break with the Union and join the Confederacy. The invasions – especially Lee’s in Maryland – were also calculated to have maximum effect on Northern voters: mid-term elections would be held in November, and Confederate victories might well tip the electoral balance against the “war party.”

Lincoln’s strategic analysis cut deeper still. He too recognized the need for stronger armies and more aggressive military offensives. But he had also become convinced that the war could not be won without a direct attack on slavery. Slavery was the basis of the South’s economic and military strength – to break the South’s ability to fight, its economy must be broken. On a deeper level, slavery had caused this war, and as long as slavery existed a new outbreak of civil war was possible. The longer, costlier war for the Union that now seemed necessary could only be justified if it removed the root cause of conflict. But it would take a revolutionary use of federal power; and it would make a compromise peace impossible.

After his complete failure in the Peninsula Campaign, why was it that Lincoln felt compelled to keep McClellan as the head of the Army of the Potomac?

RS: There were two moments when Lincoln had to face that choice. After the Seven Days, Lincoln became convinced that McClellan lacked the aggressive energy Lincoln’s strategy required. McClellan had also presented him with a political manifesto – the so-called “Harrison’s Landing Letter” – that made clear McClellan’s opposition to Lincoln’s policies in general (and anti-slavery in particular). However, McClellan still held the passionate loyalty of the vast majority of officers and men in his army. Any replacement would have been met with hostility and mistrust. He also enjoyed strong backing from the War Democrats, whose support was vital to the war effort; and his public prestige remained very high. So Lincoln passed the buck to his new General in Chief, Henry Halleck – tell McClellan he must either advance on Richmond, or face removal. But Halleck lacked the moral courage to enforce that choice. So they made the worst possible compromise: to leave McClellan in nominal command, but transfer his army piecemeal from Virginia to Washington, where it would unite with the force under John Pope.

The effect of this was to remove the threat to Richmond, and allow Lee to take the offensive against Pope, while half the Union forces in Virginia were at sea. When Lee wrecked Pope’s army at Second Bull Run, Lincoln had to face the choice a second time. His cabinet was violently opposed to restoring McClellan to command. Secretaries Chase and Stanton believed he had deliberately withheld reinforcements that might have saved Pope, and should be shot as a traitor. Although he well understood the danger inherent in McClellan’s hostility to his own government, Lincoln also knew McClellan was the only general who could get the army in shape in time to resist Lee’s invasion of Maryland. His reappointment of McClellan was an act of moral courage, equaled by his decision to fire McClellan after his victory at Antietam.

Did Robert E. Lee need to bring on a battle of annihilation for his Maryland Campaign to be successful?

RS: No – although he was willing to accept such a battle if the opportunity arose.

Lee’s objectives were a mix of military and political. He believed the Union army was badly disorganized and demoralized after its defeat at Second Bull Run. So his first move was to Frederick, MD, only fifty miles from Washington. His idea was to provoke the Federals into a hasty advance. He believed his own army, better organized and with higher morale, would at least drive the Federals back to Washington. Lee could then hold a position on northern territory for an extended period. The prestige of such a victory, and the presence of a Southern army, might move slaveholding Marylanders to quit the Union, exposing Washington to encirclement.

But if the Union generals declined Lee’s gambit, he planned to pull back westward, over the high ridges of South Mountain, to establish a permanent base around Hagerstown, MD. From there, sheltered behind the mountain wall, drawing supplies from the Shenandoah Valley, he could mount heavy raids into Pennsylvania, punishing Northerners as Virginians had been punished. This would at least relieve Virginia of Federal invasions. At best, the extended presence of a Rebel army on Northern soil might have a powerful effect on the mid-term elections scheduled for November.

In your account you indicate that Lee had come to the conclusion that the Maryland Campaign was already a failure by the time of the Battle of South Mountain. Why had Lee come to that conclusion before any decisive battle had been fought?

RS: When the Federals refused to attack him at Frederick, Lee went to his secondary plan, retreating westward over South Mountain. But in order to maintain his army near Hagerstown, he had to capture the Federal post at Harpers Ferry, which blocked his supply route through the Shenandoah Valley. To do that he had to divide his army in four parts: three of them under Stonewall Jackson to Harpers Ferry, while only some twenty thousand remained with Lee himself in and around Hagerstown – waiting for Harpers Ferry to fall. But his plans were exposed on September 13, when McClellan obtained a copy of Lee’s orders, lost by a courier. Emboldened by the discovery, McClellan advanced against the Hagerstown force and broke through Lee’s defense at Turner's Gap in South Mountain. At that point, with his force outnumbered four to one, Lee thought he had no choice but to retreat to Virginia. He had actually started his guns and wagons across the river when Jackson sent word that Harpers Ferry would fall on September 15. Lee then decided to stand at Sharpsburg with his small force, and wait for Jackson to join him.

You posit that McClellan’s decision not to attack Lee and Longstreet on September 15 actually increased McClellan’s chance for a decisive victory. Why was that?

RS: On the 15th Lee had only about 18,000 troops with him. By late afternoon, McClellan was able to concentrate about 40,000 – half of his troops were still marching up from Washington or handling other assignments. If McClellan had attacked that afternoon -- given the advantages of Lee’s defensive position, and McClellan’s defects as a tactical commander – he might well have driven Lee from his lines and forced him to retreat. It is unlikely that he could have destroyed Lee’s force. Aside from McClellan’s habitual “slows,” the Union army was not capable (at that point in the war) of mounting the kind of pursuit that destroys a retreating foe. Lee’s prestige would have been hurt, but the bulk of his army would have remained intact.

However, on the 16th McClellan would have over 60,000 troops concentrated, and another 13,000 near at hand. Lee would not have more than 25,000. Lee and Jackson had miscalculated the speed with which Jackson’s forces could disengage from Harpers Ferry and march to Sharpsburg. Only two of Jackson’s five divisions made it to Sharpsburg on the 16th. Two more divisions would not march in until 4 AM on the 17th , the day of the battle; and A. P. Hill’s Division would not arrive until 4:30 PM, while the battle was at its height. By waiting for Jackson, Lee had put much more of his army at risk than there had been on September 15. McClellan’s force still outnumbered him more than two to one, and was much better prepared for an offensive than it had been the previous day.

Put us into Lee’s mind on the eve of the Battle of Antietam.

RS: Lee’s decision to stand and fight on the 17th has been questioned. He had only about 37,000 troops at hand, against McClellan’s 73,500 – and McClellan would have the initiative. If he lost, retreat might be ruinous, since he had a river at his back with only one usable ford.

Lee’s justification for taking such risks was simple. Lee did not think the South could survive an extended war. The combination of military success and political opportunity that now existed – with every Confederate army on the offensive and northern mid-term elections approaching – that combination might never again occur. All he had to do was force the faint-hearted McClellan to retreat, and he might win the war in one afternoon. The stakes were worth the gamble.

He also had a few advantages. His positions could not be easily flanked. Lee also had “interior lines,” inside a tight arc, while McClellan’s was spread in a wider external arc. Lee could move troops and artillery – and orders – from point to point much faster than McClellan. Moreover, Lee’s subordinate generals – his corps, division and brigade commanders – were far more experienced than McClellan’s at working together. Even without orders they knew how to cooperate under the stress of combat. Like other great generals, such as Frederick the Great and Napoleon, Lee counted on his army’s superior organization and morale to overcome McClellan’s advantage of numbers. Finally, although Lee lacked the long-range heavy artillery McClellan commanded, his army was amply supplied with the short-range, infantry-killing guns that counted most heavily at the point of attack.

Much ink has been shed on McClellan’s battle plan and execution at Antietam. Where do you come out on his generalship at Antietam?

RS: McClellan’s conduct of the battle was inept. In part, this reflected lack of experience. Antietam was the first general engagement that he himself planned and initiated. In other actions he had acted on the defensive, and exercised little actual control of tactical operations. He was faced with a veteran army, in a strong position, whose commander was a master tactician, seconded by experienced subordinates. To break that army’s line he would have to mount attacks that were both powerful and well-coordinated. This he and his subordinate commanders were unable to do.

I also think politics also affected his battle plan. As always, he was at least as concerned about the Radicals in his rear as he was about the Rebels in his front. He believed that if he suffered a setback – even a temporary one – the Radicals would force him out; whereas if he simply forced Lee to retreat, he would be hailed as a savior of the Union, and his political position would be unassailable. He was therefore hyper-cautious in his battle plan, refusing to risk defeat by the kind of all-out offensive that might have won him a decisive victory. He could not muster strong, coordinated attacks, because he held most of his troops – and all of his best troops – in a central reserve position. He gave the initial offensive missions to his least experienced corps commanders (Hooker, Mansfield and Burnside), and to units he considered second-rate (that is, troops from Pope’s army). The troops in his center were three corps of Potomac veterans, “his boys” from the Peninsula Campaign, commanded by men personally loyal to McClellan (Franklin and Porter). Theoretically, this elite reserve was to provide the force that would exploit any opportunity presented by Hooker’s attack. In fact, it would take them an hour and a half to march to Hooker’s aid – too late to have decisive effect. But there in the center, they were McClellan’s “Life Guard.”

In your book you detail the many specific political considerations that went into the precise wording of the Emancipation Proclamation. What were some of these considerations?

RS: The political considerations were a mixture of the grand, the partisan, the legal and the tactical. Lincoln was careful to rest his authority to issue the proclamation on his constitutional powers as commander-in-chief, which required him to take all actions in his power necessary to preserve the nation, the government, and the laws. That legal constraint partly explains the limitation of emancipation to slaves in Rebel-held territory; but it also suited his on-going efforts to both retain the loyalty of the slave-holding Border States, and at the same time persuade (or pressure) them to voluntarily abolish slavery. He also included a few lines recommending the colonization of freed slaves abroad, as a sop to conservatives in his own party (like Attorney General Bates) as well as to Democrats. However, the colonization passage was much shorter and weaker than it had been in his first draft, presented to the cabinet back on July 22.

The most interesting considerations have to do with timing. Everyone knows that Lincoln, on Seward’s advice, delayed issuing the Proclamation until the Union armies had won a victory. That had delayed issuance from July 22 till September 22, five days after Antietam. But a more interesting timing consideration is the deadline of December 31, 1862, for Southern states to give up their rebellion and save their slave property. That deadline was unchanged from the first draft, written on July 22. If issued then, the South would have had six months to come to terms. But by September 22, less than three months remained till the deadline. It still gave the Proclamation the appearance of an ultimatum, which won the support of some conservative newspaper editors, who urged the South to accept the offer. But the term was ridiculously short. It seems clear that the ultimatum was pro forma. Lincoln never expected the South to accept. In issuing the Proclamation he knowingly embraced a war to the finish.

Civil War Trust: In your assessment what made the Emancipation Proclamation “revolutionary”?

RS: Its expansion of presidential powers was revolutionary. Lincoln asserted that as commander-in-chief, he had the power to confiscate the property of citizens inhabiting rebellious districts, without judicial proceeding. In purely economic terms, this was expropriation on a colossal scale. At a stroke of the pen some 3.5 billion dollars’ worth of property was legally annihilated – this at a time when national GDP was less than 4.5 billion, and national wealth (the total value of all property) about sixteen billion dollars. It guaranteed that if the Union was restored Southern society would be revolutionized.

Two codicils had especially radical implications. One enjoined Blacks “to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense.” This was intended to offset the accusation that Lincoln was fomenting a “servile insurrection” and race-war. But by suggesting that Blacks could use violence for self-defense, the proclamation attacked the fundamental principle of plantation law and discipline, which absolutely forbade the slave to physically resist abuse by a legal master, and even denied the slave the right to appeal to a court.

More radical still was the declaration that freed slaves “will be received into the armed service of the United States.” The right to participate in the common defense is a civil right which not even the free states then recognized. As Frederick Douglass said, “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pockets, and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship in the United States.” A total of 180,000 Black men would serve, roughly 9% of the two million total Union armies enlistments, and their actual contribution was significantly greater, since these enlistments were concentrated in the last two years of the war, when the total strength of the Union armies varied between 700,000 and one million men. The war would have been lost without them.

You point out that the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation was initially a setback for the Lincoln Administration and a boost for the Confederacy. Why was this?

RS: The initial political result was mixed. Although the most radical Republicans thought it was weak, they accepted it, and eventually joined the rest of the party in thinking it a historic, necessary, and morally purifying act. However, reaction against even limited abolition probably helped the Democrats increase their share of Congressional seats and governorships in the mid-term elections. But the destruction of slavery, which the Proclamation presaged and the war made inevitable, shifted the emphasis in Northern politics from “slavery” to race. The Democrats would mount a powerful threat to Lincoln’s presidency, with McClellan as candidate, in 1864, on a platform based on war weariness and the passionate defense of white supremacy.

In the South, its effects were also two-sided. In material terms, the Proclamation undermined the plantation economy, as slaves fled plantations at the approach of Union armies, or added their strength to those armies. But Confederate leaders were able to hold their war-weary and suffering people to a failing cause, by appealing to their fear and hatred of Negro equality.

Some historians have cited the Proclamation as a decisive factor in keeping the British from intervening on the Confederate side. That seems not to have been the case. Brits who recalled the horrors of the Sepoy Mutiny (1857) were repelled by what they saw as a licensing of “servile insurrection” and race war. The British government did not give up on intervention until they were sure the South was losing the war.

In researching this book did you have a chance to visit many of the 1862 Maryland Campaign sites? Which are your favorites?

RS: The Antietam battlefield itself may be the best-preserved major battlefield in the country. It’s moving, and illuminating, to stand on the ground, and try to see things as the participants might have seen them.

Buy the Book: "The Long Road to Antietam" is available from our Civil War Trust-Amazon Bookstore

Richard Slotkin (born 1942) is a cultural critic and historian. He is the Olin Professor of English and American Studies at Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT, and in 2010 was elected a member of the Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1995 he received the Mary C. Turpie Award of the American Studies Association for his contributions to teaching and program-building. Slotkin writes novels alongside his historical research, and uses the process of writing the novels to clarify and refine his historical work.

Related Battles

12,401

10,316

2,325

2,685