The Battle of Second Manassas: Then & Now

John Hennessy, Chief Historian for the Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, and the author of the definitive book on the Battle of Second Manassas (Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas), sat down with us to discuss the history and modern memory of this important Civil War battle.

Civil War Trust: Set the stage for us. Where does Second Manassas sit in relation to, say, the Seven Days and Antietam?

John Hennessy: We like our events to be the beginning or the end of something. Though it was the largest battle in the Eastern Theater up to that time, Second Manassas was neither a beginning nor an end, and so historians and the public have tended to look beyond it. First Manassas, on the other hand, was wrapped in as much drama and public attention as any event in American history. We are fascinated by it still.

The campaign and battle of Second Manassas re the bloody bridge spanning the end of the Peninsula Campaign and the dreadful climax of the year's spring and summer's campaigning at Antietam. Still, Second Manassas is a profoundly instructive story in its own right, coming as it did in the midst of Lincoln's efforts to change the nature of war in Virginia, to supersede McClellan by winning a victory at Pope's hands, and to do deal a devastating defeat to Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. Any of these things required victory, and the Union failure at Second Manassas left the Union war effort staggered.

I'd also add here something I've often pondered: Lee followed his victory at Manassas by doing the one thing that could re-energize that demoralized Union army--crossing the Potomac onto Northern soil. One can't help but wondering what might have happened had the Union defeat--and all the political drama surrounding it--been allowed to fester. Alas, events moved so swiftly and spectacularly that by the time the armies clashed on Antietam Creek, Second Manassas seemed a distant memory to much of the nation.

Can you compare and contrast the two armies and the commanders at Second Manassas?

JH: While the differences between Lee and Pope were profound, it does not follow that this was a mismatch of comical proportions, as is often suggested. Pope was generally smart and efficient, thoughtful and reliable (though boastful)--and in the early stages of the campaign here performed creditably. But as events spun to a climax, he descended into the unimaginative, unable to put himself into his foes shoes. Instead, he presumed Lee would do what Pope wished him to do; conversely, Pope invariably did precisely what Lee hoped he (Pope) would do. And that was a recipe for disaster for a Union general.

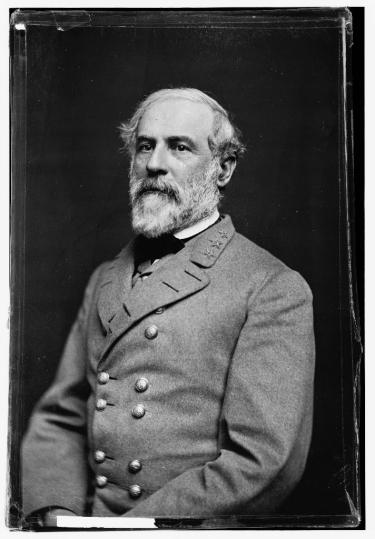

This was Lee's first full campaign--the first of his creation. He faced incredible pressures of both time and space (with two armies rushing to unite before him), but he reacted with careful, rational thinking and planning that most of us could only envy today. Contrary to some recent scholarship, Lee was not hell-bent on attacking Pope at Second Manassas, but rather was intent on attacking only when and if a near-perfect opportunity to destroy the Union army presented itself. That opportunity presented on the afternoon of August 30, and Lee came as close as he ever would to destroying a Union army in the field.

What are some of the terrain features at Second Manassas? Is it just roads and open fields?

JH: The battlefield was a typical agricultural landscape like thousands of others across America made notably only by what happened there. It was dotted with farms small and mid-sized, fields and woodlots and a road network that connected tiny hamlets and mini-centers of industry and commerce (like Groveton and Sudley). The regional road network pointed the armies in the battlefield's direction, but ultimately the presence of an unfinished railroad line north of the Warrenton Turnpike determined both the nature and location of much of the battle. Jackson used the unfinished railroad as the focal point for a 1.5-mile long defensive line. For two days fighting raged along Jackson's front, most spectacularly in the area around the "Deep Cut" on August 30--some of the most intense, close fighting of the war.

The tract we are trying to save figures in the fighting on August 28 and August 30. Why were they fighting in this specific area?

JH: Jackson's decision to use the unfinished railroad as a defensive position doomed the farms in front of it--in this area, Lucinda Dogan's--to become killing fields. On August 28, the battle lines spilled from John Brawner's Farm onto Lucinda Dogan's, extending nearly all the way to the Dogan Parcel the Trust is now hoping to acquire. Indeed, Richard Ewell was disastrously wounded very near this parcel.

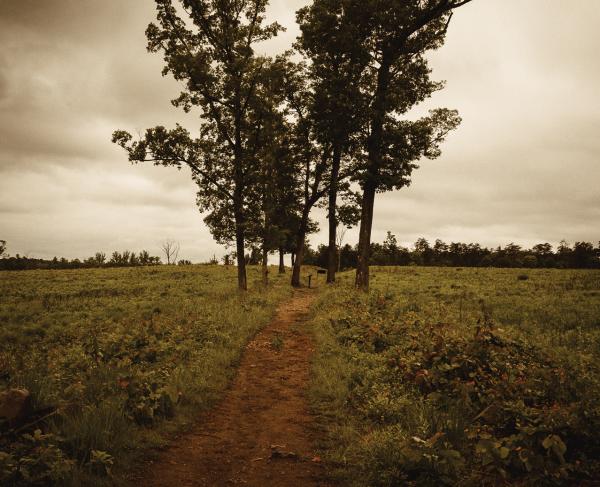

On August 30, Porter's troops launched the largest Union attack of the battle across Mrs. Dogan's farm. For years the NPS has owned the land directly in front of the Deep Cut, but that land embodies only about two-thirds of the Union front as it advanced on August 30. The Dogan tract now under consideration by the Trust is as important a piece of hallowed ground as exists at Manassas. With the clearing the NPS has done around this parcel in recent years, its thick (and non-historic woods) now stand like an ink spot on an otherwise vivid canvas. Personally, I can think of no parcel I'd rather see preserved than this one.

Do you have a favorite story associated with Second Manassas?

JH: It's hard to fathom a favorite amidst something as dreadfully tragic as a battle, but amidst all that horror we can also sometimes see the virtue in man. I have always been mightily impressed by the actions of McLean's Ohio brigade on Chinn Ridge on the afternoon of August 30, as they bought with lives precious minutes that allowed the Union army to build a final battle line on Henry Hill.

I am struck too by the actions of Pennsylvanian Mark Kerns, who in resisting Longstreet's attack on August 30 stood by his guns after all his men had run away. The Confederates beseeched him to surrender. He refused, and was shot down. When the Confederates approached him he declared, "I promised to drive you back or die under my guns, and I have kept my promise." Then he died. Why do men do such things?

I also marvel at the management of the campaign by Lee--the careful measures of risk and security, the imagination, and the wise use of the tools available to him (especially Jackson). In many ways, Lee is the model for a modern manager.

Learn More: The Battle of Second Manassas

John Hennessy started his National Park Service career at Manassas National Battlefield Park in the early 1980s and has since written books on both battles, including Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas. He is presently the Chief Historian at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

Related Battles

14,462

7,387