The Battle of Glendale and the Gravel Hill Community

Bert Dunkerly

Richard Sykes would never forget Saturday, June 30, 1862. The 56-year-old, free African American farmer awoke the day before to find thousands of soldiers near his small farm at Gravel Hill along the Long Bridge Road, about ten miles from Richmond.

The path to that moment began shortly before the Revolutionary War, when Quaker John Pleasants freed his slaves in his will. His son sought the help of lawyer John Marshall to carry out his wishes, and eventually 78 enslaved people were freed and given 350 acres of land near Glendale. They settled there, naming the community Gravel Hill after the texture of the region’s landscape.

Like other free African Americans in Virginia, residents of Gravel Hill were subject to conscription to support the Confederate war effort. For example, William James, a charcoal handler, was drafted to work on Confederate defenses. James escaped and eventually made his way to the Union supply base at City Point, where he worked for the Quartermaster Department.

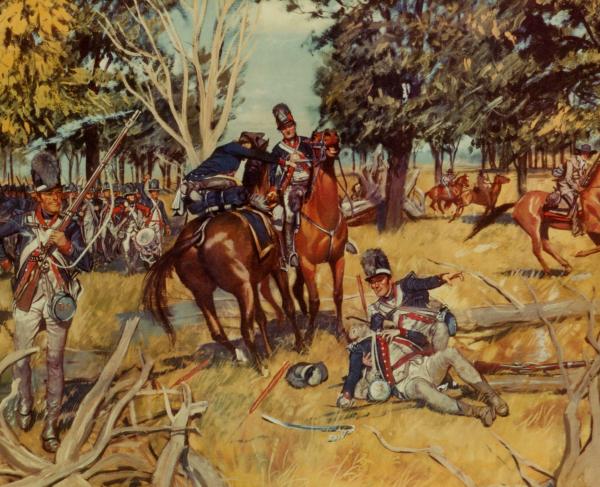

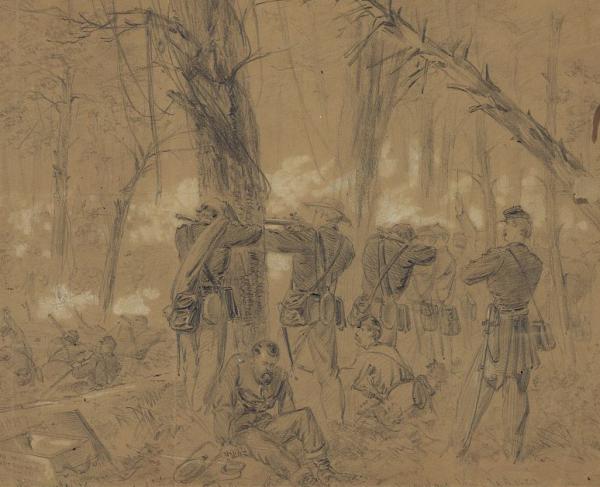

Richard Sykes and his brother Isaac lived side-by-side near the crossroads of Glendale. On the afternoon of June 29, Union troops arrived and camped on the edge of Richard’s farm. The next day, fighting raged across their farms as the crossroads at Glendale became the target for Gen. Robert E Lee’s army. As the Pennsylvanians of Brig. Gen. George McCall’s division hastily formed for battle on the edge of their property, Richard, his wife Mary, and their three children (aged 4, 10, and 22) fled from their home with a few belongings. They reached the safety of some woods. Then came “a dreadful crash, as if the sky had fallen and all the thunders I ever heard had been rolled into one.” Falling to the ground in terror, they were soon struck by falling branches ripped off the trees overhead. As Richard led them away from the developing battle, one child, stricken with fear, had to be carried.

About 900 men were killed and 5,400 wounded on both sides during the fierce, four-hour struggle at Glendale. Many of them lay scattered over the farms of the Sykes brothers, as well as the Atkins, James, Pleasants, McDowell, and Whitlock properties. The Sykes farms were devastated. Isaac later claimed the loss of a horse, cow, four acres of oats, five acres of corn and 11,000 fence rails. He claimed more than $2,000 in damages, but was awarded only $303. Like many of the residents of Gravel Hill, Isaac claimed he was a Union man and “was willing to help it with all my heart.”

Following the war, residents founded Gravel Hill Baptist Church in 1866, with Richard Sykes serving as deacon. In the 1930s, the county built a school for the area’s students, which closed by 1970. Now a community center, it houses exhibits on the history of Gravel Hill. Many descendants of those residents from 150 years ago still reside here. In 2006 the Civil War Trust launched an effort to preserve the Glendale battlefield, including the site of the Sykes brothers’ farms. In one of the most successful efforts in battlefield preservation to date, nearly the entire Glendale Battlefield has been preserved.

There are 29 critical acres of battlefield land in Virginia, at Glendale, and at Gaines’ Mill/Cold Harbor that we have the opportunity to save in...

Related Battles

3,797

3,673