Battle of Ball's Bluff: Then & Now

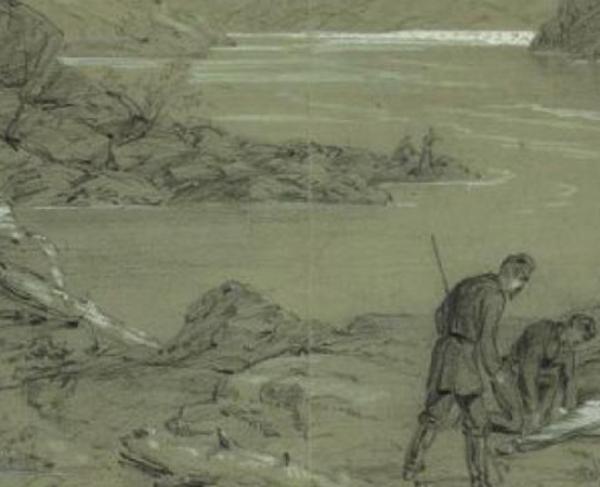

The Civil War Trust turned to Jim Morgan, the expert on the Battle of Ball's Bluff, for more details on the 150th anniversary on this important 1861 battle.

Civil War Trust: Help us better understand the strategic situation leading up to the Battle of Ball’s Bluff on October 21, 1861. What were both sides attempting to do at this time?

Jim Morgan: For much of the post-Manassas period both sides focused on rebuilding. Generally speaking, things were, as the song said, “all quiet along the Potomac.” Certainly, that was the situation in Loudoun County, Virginia, and Montgomery County, Maryland.

Remember that where the Potomac forms the boundary between those two counties, there are numerous fords which could have been used by either side. That made the whole area strategically significant. Union and Confederate pickets spent the three months after First Manassas watching those fords but did so in a state of what might be called relaxed wariness. They occasionally took potshots at each other but were just as likely to establish local truces of the sort that became so common during the war.

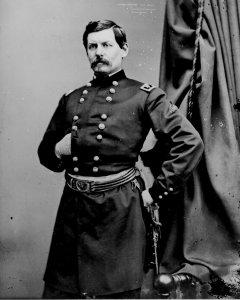

Things began to change in October, however. Brig. Gen. Charles P. Stone, in command of the Union Army of the Potomac’s right flank division along the Potomac line, received a large reinforcement during the first few days of that month. Colonel (and U.S. Senator) Edward D. Baker arrived with a four-regiment brigade known, somewhat misleadingly, as the “California Brigade.”

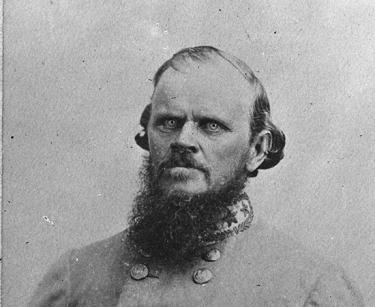

Colonel Nathan “Shanks” Evans, commanding the Seventh Brigade of the Confederate Army of the Potomac (it wouldn’t become the Army of Northern Virginia for several months), understood that he was at a distinct disadvantage. He had roughly 2800 troops facing Stone’s three Union brigades which, with Baker’s arrival, numbered about 10,000 men. Fortunately for him, Stone’s mission at that time was merely to watch the river. Indeed, his division was called the “Corps of Observation.”

The situation became even more ominous for Evans on October 9-10 when Union Brig. Gen. George McCall brought another Federal division of 12,000 men across the river and established “Camp Pierpont” at Langley, Virginia, some 25 miles east of Leesburg. Evans commanded a tripwire force that was 25-30 miles away from the nearest Confederate reinforcement. Thus, he became very concerned about the possibility of being enveloped by an overwhelming Union force should McCall advance from the east and Stone cross the river.

One might say that Shanks Evans got spooked by this possibility and by some minor fighting that took place upriver from him at Harper’s Ferry on October 16. It seems as if he might have interpreted that fighting as the beginning of the envelopment he’d feared. In any case, he packed up his brigade and abandoned Leesburg, without orders from his superiors, beginning around midnight on October 16-17, heading south more or less along today’s Route 15. It was not until the next day that he informed General Beauregard of this action.

Not surprisingly, Beauregard was not pleased to hear that Evans had left those strategically significant fords unguarded and virtually had conceded Leesburg to the enemy. He chided Evans for doing so and, by October 19, Evans had returned.

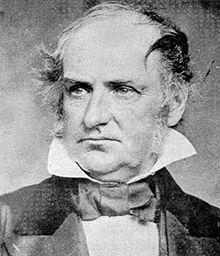

In the meantime, the Federals had noticed his absence and reported to General McClellan who suspected that Evans’ withdrawal might be a trap. He ordered General McCall to make a reconnaissance-in-force with his entire division as far as Dranesville, about halfway to Leesburg, then to probe from there. As it turned out, by the time that McCall arrived in Dranesville, Evans was back in Leesburg, lined up east of town along Goose Creek waiting for what he thought would be a strong Union advance against his much smaller force.

McClellan didn’t like the looks of the situation, however, and, on the evening of October 19, ordered McCall to return to Langley the next morning. McCall asked for an extra day to finish some maps he was having made and McClellan granted the request. Thus, on October 20, the day before the battle, McCall was still hovering around the eastern approaches to Leesburg but preparing to leave the area. Evans was trying to keep up his men’s spirits for the attack he believed was about to happen. And Stone was not really part of this picture yet at all.

George McClellan had ordered Brig. Gen. Charles Stone to conduct a “slight demonstration” on the Maryland side of the Potomac River to evaluate Confederate intentions. How was it that this small reconnaissance blossomed into a deadly fight on October 21st?

JM: McClellan informed Stone on October 20 that McCall was in Dranesville. Significantly, he did NOT tell Stone that he’d already ordered McCall to withdraw to Langley the next morning. All day on October 21, as the battle of Ball’s Bluff was developing, Stone thought that McCall’s 12,000 men were only a few miles away and might possibly be coming. Instead, those men were marching in the other direction and knew nothing of the fighting.

But McClellan did order Stone to conduct a “slight demonstration,” suggesting that this and McCall’s movements might together induce the Confederates to leave. Stone moved troops very visibly down to the river at Edwards Ferry and put boats into the water in order to convince the Confederates that he was about to cross. He moved other troops to various locations along the river, in effect prepositioning resources in case he needed them. There was no plan for an attack, however. This was only a feint to determine what the Confederate response might be.

At the end of the day, nothing had happened. Evans had watched but not reacted. At dusk, Stone pulled his troops back from Edwards Ferry and the story might very well have ended there.

Stone then ordered a small reconnaissance patrol to cross the river from Harrison’s Island opposite Ball’s Bluff to determine what effects all of this moving and feinting might have had. The patrol, some 20 men from Company H, 15th Massachusetts, crossed the river shortly after dusk, advanced out into the area of today’s Potomac Crossing subdivision, and made an amateurish, but critical, mistake. Capt. Chase Philbrick saw in the dim moonlit distance what he believed to be the tents of a Confederate camp. Without verifying this, he returned and reported this information to General Stone. What Philbrick in fact had seen was a row of trees.

It was this bit of faulty intelligence information on which Stone based his decision to cross more troops, a 300-man raiding party with orders to raid the “camp” and return. Historians often have confused this raid with the demonstration though it was a separate event. The troops crossed during the night, discovered the mistake the following morning, and soon engaged a small Confederate picket force from Company K, 17th Mississippi in what became the opening round of this totally unplanned battle.

The Battle of Ball’s Bluff is famous as the only battle in American history where a sitting U.S. Senator was killed in battle. How was it that Colonel and U.S. Senator Edward D. Baker came to be involved in the fighting at Ball’s Bluff?

JM: Senator Edward D. Baker had become Colonel Edward D. Baker when his “California Brigade” was organized earlier in the year. He was ordered to Stone’s division as part of the overall buildup of the Federal army. On the morning of October 21, Baker rode to Stone’s camp to ask what all the activity was about. He had learned of the raiding party but his own troops were not involved so he went to Stone essentially to be briefed.

By then, Stone had learned of the mistake about the trees and had decided to turn the raiding party, still across the river in Virginia, into an expanded reconnaissance by ordering other troops across. Again, this was not pre-planned and was not part of an attack on Leesburg. It was Stone’s response to events. When his raiding party had realized there was no camp to raid, Col. Charles Devens reported back that things looked quiet and he saw no enemy. Stone decided to reinforce Devens, then have him move closer to Leesburg to find out if the Confederates had left.

Stone ordered Baker to go to Ball’s Bluff and take command of what both men believed to be nothing more than a reconnaissance. He told Baker to evaluate the situation and then decide whether to cross still more troops or withdraw those already there. In fact, the opening skirmishing had taken place but neither Stone nor Baker knew it.

While on his way upriver to implement his orders, Baker ran into a messenger from Colonel Devens, commander of the raiding party, informing him of the skirmishing. The messenger then continued on to General Stone while Baker became very offensive-minded and began ordering all the troops he could find to cross the river. Eventually, though not for about four hours, Baker crossed over himself, by which time additional and heavier skirmishing had taken place as Shanks Evans responded to the crossing of Union troops by sending troops of his own to meet them.

Baker thus got involved in the fighting only because Stone had put him in command of what was supposed to be a reconnaissance. He just happened to show up at Stone’s headquarters at the right (or wrong) moment. His involvement in this action, like the battle of Ball’s Bluff itself, was accidental.

One of the Union regiments involved in the battle was the 1st California. You don’t hear of many California regiments being involved in Civil War battles. How did a unit of Federals from the far west find themselves on the bluffs above the Potomac in October 1861? How did they perform?

JM: The irony here is that these “California” troops mostly were from Pennsylvania.

Edward Baker had spent much of the 1850s in California and was identified in the public mind with that state. When war came, however, he was in Washington as a senator not from California but from Oregon.

Shortly after Fort Sumter, Baker and some other men with west coast connections began an effort to symbolically tie the west coast to the Union by having organized bodies of troops from the two west coast states as part of the Union army. But it would take too long to move troops that distance (no railroad west of the Mississippi) and no one expected the war to last very long anyway. So Baker helped organize a massive rally in Union Square in New York City in April, 1861, the purpose of which was to enlist “West Coast Men” into “Baker’s California Regiment.” It is doubtful that anyone checked very closely to make sure that his enlistees actually were west coast men. The goal was simply to have a unit with the California name.

The recruiting effort had some success but Baker had to return to his senatorial duties in Washington. He contacted a former California law partner of his then living in Philadelphia, Isaac Wistar, and asked him to take over the organization of the regiment. Wistar agreed but wanted to do it in Philadelphia instead of in New York. With Baker’s approval, he went to work and succeeded so well that the proposed single regiment became four regiments collectively styled the “California Brigade.”

Through an oddity of timing and organization, the four became known as the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 5th California regiments. Colonel Baker became the brigade commander and Lt. Col. Wistar took over the original California regiment, the 1st California.

About half of the 1st California took part in the battle of Ball’s Bluff. The rest of the brigade, like other troops in Stone’s division, stood in line on the Maryland side of the river waiting to be shuttled over on the limited number of boats that were available for this unplanned river crossing.

The “Californians” fought well but were overwhelmed in the end along with the men from Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island who made up Baker’s scratch force at Ball’s Bluff.

Baker, as you know, was killed in the battle. Governor Andrew Curtin of Pennsylvania took advantage of this to have the four regiments renamed with Pennsylvania designations. They became, respectively, the 71st, 69th, 72nd, and 106th Pennsylvania. The California Brigade became known as the “Philadelphia Brigade” and went to glory in Antietam’s West Woods and at Gettysburg’s Copse of Trees.

Interestingly, the 1st California, even after being renamed the 71st Pennsylvania, continued to call itself the “California Regiment” throughout the war. That name is carved onto its monument at Gettysburg.

There also has been some confusion on occasion between the California Brigade and a completely different unit known as the “California Hundred.” Those men were, in fact, Californians who came east, eventually becoming part of the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry. They are unrelated to Baker’s unit and had nothing to do with Ball’s Bluff.

The fight at Ball’s Bluff would involve roughly 1,700 troops on both sides. Given the equal numbers, how was it that this 1861 battle ended in such an uneven Union rout?

JM: Command decisions and terrain. First of all, Colonel Baker, on learning of the fighting around 10:00 a.m., did not immediately go over to Ball’s Bluff himself, but remained on the Maryland side doing a job he should have turned over to a subordinate; he went looking for boats. But not only did he not cross the river himself for nearly four hours, he put no one in overall command on the Virginia side and he issued no orders about what to do when the various units got there.

All the early skirmishing was done some distance inland by Col. Charles Devens and the 15th Massachusetts against growing numbers of Virginia and Mississippi troops. The other Federals who crossed simply deployed along the bluff and waited.

Baker finally arrived on the field shortly after 2 p.m. and was advised by several officers, including Col. Milton Cogswell of the 42nd New York, the only West Pointer in the Union command structure that day, that he should move his entire force forward, away from the bluff, and up the slope that leads past today’s parking lot and into the area where the subdivision now sits. Had he done that, his men could have deployed more effectively and, of course, would not have had the bluff at their backs. Baker refused and kept his men in what was effectively a cul-de-sac, the only way out being over the bluff behind them.

Moreover, he deployed his men in several lines, mostly in the open field that existed at the time. Thus, the men in the rear ranks could not fire but the whole mass of men made a wonderful target for the Confederates.

Shanks Evans, on the other hand, made good decisions. As the day progressed, he gradually moved troops away from Edwards Ferry and to Ball’s Bluff without letting the Federals know that he was weakening one flank to strengthen the other. In addition, for the most part, the Confederates controlled the high ground and had room to maneuver. They also had the initiative which Baker had given up when he decided to fight a purely defensive battle.

The Union reaction to the debacle at Ball’s Bluff would lead to the creation of the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. What were the key findings and outcomes of their investigation of the Battle of Ball’s Bluff?

JM: Ball’s Bluff was the final straw that led to the creation of the Committee. Remember, Union forces had been beaten at Manassas in July, at Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, in August, and at Ball’s Bluff. Enough was enough.

Ostensibly, the Committee intended to investigate the causes of the defeats but, very quickly, the “Radical Republicans” who dominated Congress, that is, the hard core abolitionists who were pushing Lincoln to turn the war into an anti-slavery crusade right away, began going after officers who were not considered anti-slavery enough; in particular, friends of General McClellan.

The Committee was organized and opened its hearings in December, 1861. Its first topic was Ball’s Bluff and its first target was General Charles P. Stone. McClellan had publically exonerated Stone three days after the battle and stated that the fault for the defeat lay not with him but with Colonel Baker. This was true but was not what Baker’s Senate colleagues wanted to hear.

More to the point, I believe that Stone would have survived the onslaught of criticism that came down on his head had it really only been about Ball’s Bluff. His actions on the day of the battle are entirely defensible. In fact, however, the battle was merely the hook on which Stone’s critics hung their complaints.

About a month after the battle, Stone returned two runaway slaves to their Maryland master. The Federal Fugitive Slave Law, Maryland’s state fugitive slave law, and Lincoln Administration policy all demanded that he do this. Aside from the existing law, the Administration had to placate Maryland slave owners as part of its plan to prevent Maryland from seceding. Slaves who escaped from Virginia owners were free to go. Slaves who escaped from Maryland owners were returned.

It happened that the job of returning the two runaways fell to some troops from the 20th Massachusetts. One of them complained to Governor John Andrew and Senator Charles Sumner, both of whom responded with blistering criticism of the act. Stone got caught in the middle.

On December 18, Sumner attacked him in a speech on the Senate floor, totally ignoring the fact that Stone was obliged to uphold existing law. Sumner apparently also was writing to officers under Stone encouraging them to disobey any future orders to return slaves. Stone had faced other criticism about this as well as about the defeat at Ball’s Bluff and had not responded up to that point. But Sumner’s speech and particularly his encouragement of insubordination among the troops were too much to ignore.

Stone responded with a very harsh note, delivered to Sumner on Christmas morning, calling him a “well known coward” and, in effect, challenging him to a duel. It was the worst mistake of Stone’s life.

Sumner was not a member of the Committee but his friend and political ally, Ben Wade of Ohio, was the chairman. The sequence of events is somewhat cloudy but I believe that Sumner instigated the attacks on Stone, assisted by Wade who made use of the Committee to give the whole thing a legal face. The Committee interviewed men from his command, most of whom had not been present at Ball’s Bluff, about the battle and about what other men thought of him. It accepted hearsay as evidence and listened to hostile witnesses accuse Stone of incompetence and of treason. The star witnesses were two officers whom Stone previously had punished for various breaches of military discipline. Both men had axes to grind but the Committee did not care.

Senator Wade, in turn, used Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to enforce the Committee’s private decision to get rid of Stone and, in February, 1862, to arrest him. Stone spent six months in prison with no charges ever filed against him and was released essentially because the war had moved on and he had served his purpose. All of this, of course, ruined Stone’s army career and eventually caused him to have a nervous breakdown.

In researching your book, A Little Short of Boats: The Fights at Ball's Bluff and Edward's Ferry, October 21-22, 1861, did you encounter any myths or misconceptions about the battle that you were able to set straight in your narrative?

JM: Quite a few; some minor, some highly significant.

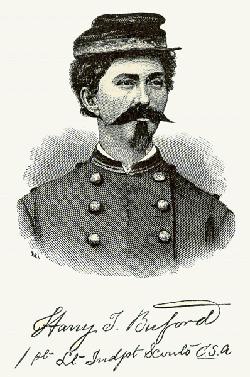

Among them is the preposterous story of Loreta Velasquez, a woman who, after the war, made a living telling of her exploits as a Confederate soldier. Claiming to have disguised herself as “Lt. Harry Buford,” Velasquez wrote that she was present at Ball’s Bluff and took command of a Confederate company that had lost all of its officers, leading that company through the battle. Some historians have accepted her tale at face value though it always has been quite easy to disprove.

There was no “Lieutenant Buford” associated with Evans’ brigade in any capacity or mentioned in any source other than Velasquez’s book. No hitherto unknown officer could have arrived in Leesburg, lived as part of the brigade for several weeks with no assignment and no orders, and not have attracted attention (and probably suspected of being a spy). Yet this is what Velasquez claims to have done. Not surprisingly, she never identifies the company she claimed to lead or the regiment of which it was a part. In any case, no Confederate company at Ball’s Bluff came remotely close to losing all of its officers. The story is a complete fabrication.

My personal favorite is really just a quibble but it has the effect of fingernails on a blackboard to me. I mentioned above that the original reconnaissance patrol mistook a row of trees for Confederate tents. For some reason, various stories changed the trees to haystacks and that version gained wide acceptance. It is a tiny detail to be sure, but the yanks did not see haystacks. Two eyewitnesses described the trees.

Most importantly, there is the pervasive myth that Ball’s Bluff was a pre-planned attack on Leesburg. The only documented evidence of any Union plan to take the town points to one written by General Stone in January, 1862, three full months AFTER Ball’s Bluff. Moreover, we know from the orders to the Federal troops that none crossed the river on October 21 with Leesburg as their goal. The force at Ball’s Bluff itself was a 300-man raiding party. The one at Edwards Ferry was a 30-man cavalry diversion. And McCall’s division in Dranesville was about to turn around and march away. No one was planning to attack Leesburg. Yet, this interpretation has dominated the telling of the Ball’s Bluff tale over the years and has led to further misinterpretations.

It is understandable up to a point. It was known on both sides that the Federals would attempt to avenge Bull Run and move “on to Richmond” sooner or later. Colonel Evans had been concerned for some time about an attempted Federal envelopment of his small force. On the morning of October 21, Evans would have known only that McCall’s division was in nearby Dranesville and that Union troops had crossed the river at Ball’s Bluff and Edwards Ferry.

This must have looked like the very envelopment he had feared. That is how he treated it and reported it. That is how history has told the story across the years. But the expectations and the appearances were misleading.

There was no plan and the battle had nothing to do with taking Leesburg. The simple fact is that Ball’s Bluff evolved from General Stone’s initial reaction to the faulty intelligence report provided by the inexperienced Capt. Chase Philbrick on the night of October 20. It developed into much more than was ever intended, but it was an accident.

Loudoun County, Virginia has long been one of the fastest growing counties in America. What is the state of the Ball’s Bluff battlefield today?

JM: Ball’s Bluff is in pretty good shape today. It actually can be called a preservation success story even though the portions of the battlefield on which the early morning skirmishing took place have been lost to development. The Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority now controls 223 acres of the original battlefield, including all the key areas. Together with the Ball’s Bluff National Cemetery, this land makes up the Ball’s Bluff Battlefield Regional Park.

The volunteer guide group’s occasional work days (one of which is held each year as part of CWPT’s Park Day) and the energetic leadership of the park manager, George Tabb, have resulted in cleaning up a badly overgrown field, partially restoring it to its 1861 appearance, and making it much easier to interpret and understand. Of course, this is an ongoing project, however, so the work will continue.

What can a visitor to the Ball’s Bluff battlefield see today?

JM: Well, there is no visitor center though we hope for something like that in the future. In September of 2007, the sixteen old, battered, and in some cases inaccurate signs were replaced by twenty new, updated signs. There are several new interpretive trails named after battle participants to make them easier to identify. There are new NVRPA park trail map brochures (access here). With this, visitors may take a detailed tour of the battlefield on their own even when the guides are not present.

The centerpiece of the battlefield park is the nation’s third-smallest national cemetery. The smallest is on the grounds of the VA Medical Center in Hampton, Virginia; it has 22 interred. Battleground National Cemetery in Rock Creek Park, Washington, DC has 41. Ball’s Bluff has 54; all Union but only one identified. In fact, the other 53 sets of remains are only partial remains recovered in 1865 after years of being scattered by weather and scavenging animals. There are 25 graves in the cemetery, 24 of which contain partial remains of more than one man. Only Pvt. James Allen of the 15th Massachusetts has been identified and has his own resting place.

Guided tours are offered between April and October, Saturday and Sunday at 11:00 and 1:00. These are free and generally last 60-90 minutes depending on weather, numbers of people, and other factors. Special holiday tours are also scheduled and group tours may be arranged by contacting the NVRPA. And we have begun the practice of having a battlefield illumination (think Antietam only smaller) every year around the anniversary of the battle. Information about this and other programs can be found on the website (Ball's Bluff Battlefield park website).

Looking into the future, what sort of battlefield developments or improvements would you like to see at the Ball’s Bluff Battlefield?

JM: The main improvement we dream about is a visitor center though that probably won’t happen any time soon. In the meantime, the volunteers will continue to interpret the battle and come out on work days to haul away deadfall, mulch the trails, and bring the field back as close as possible to its 1861 appearance.

Learn More: Ball's Bluff

A lifelong Civil War enthusiast, Jim Morgan was born in New Orleans, grew up in Pensacola, Florida, and now lives in Lovettsville, Virginia. His Confederate ancestors served in the Pointe Coupee (La.) Artillery, the 6th Louisiana Battery, and the 41st Mississippi Infantry.

Jim is past president of the Loudoun County Civil War Roundtable and a member of the Loudoun County Civil War Sesquicentennial Committee. He is a volunteer battlefield guide at Ball’s Bluff and recently has joined the advisory board of the Mosby Heritage Area Association.

His tactical study of Ball’s Bluff, titled A Little Short of Boats: The Fights at Ball's Bluff and Edwards Ferry, October 21-22, 1861, was published in 2004 and has been called “the definitive account of Ball’s Bluff.” Jim also has written for Civil War Times, America’s Civil War, Blue and Gray, and The Artilleryman among others. His accounts of Ball’s Bluff appear on the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority website (nvrpa.org) and the Journey Through Hallowed Ground website (hallowedground.org). He currently is researching a biography of Union Brig. Gen. Charles P. Stone.

Jim holds a master's degree in Political Science from the University of West Florida and a master's in Library Science from Florida State University. He works as the Acquisitions Librarian for the State Department's Office of International Information Programs in Washington, D.C.

Related Battles

1,002

155