Why Non-Slaveholding Southerners Fought

Gordon Rhea

This year initiates the commemoration of the Sesquicentennial of the Civil War. This is an occasion for serious reflection on a war that killed some 600,000 of our citizens and left many hundreds of thousands emotionally and physically scarred. Translated into today’s terms – our country is ten times more populous than it was then -- the dead would number some 6 million, with tens of millions more wounded, maimed, and psychologically damaged. The price was indeed catastrophic.

As a Southerner with ancestors who fought for the Confederacy, I have been intrigued with the question of why my ancestors felt compelled to leave the United States and set up their own country. What brought the American experiment to that extreme juncture?

The short answer, of course, is Abraham Lincoln’s election as president of the United States. What concerned Southerners most about Lincoln’s election was his opposition to the expansion of slavery into the territories; Southern politicians were clear about that. If new states could not be slave states, went the argument, then it was only a matter of time before the South’s clout in Congress would fade, abolitionists would be ascendant, and the South’s “peculiar institution” – the right to own human beings as property – would be in peril.

It is easy to understand why slave owners would be concerned about the threat, real or imagined, that Lincoln posed to slavery. But what about those Southerners who did not own slaves? Why would they risk their livelihoods by leaving the United States and pledging allegiance to a new nation grounded in the proposition that all men are not created equal, a nation established to preserve a type of property that they did not own?

In order to find an answer to this question, please travel back with me to the South of 1860. Let’s put ourselves into the skin of Southerners who lived there then. That’s what being an historian is about: putting yourself into the minds of people who lived in another time to understand things from their perspective, from their point of view. Let’s set aside what people said and wrote later, after the dust had settled. Let’s wipe the historic slate clean and visit the South of 150 years ago through the documents that survive from that time. What were Southerners saying to other Southerners about why they had to secede?

There is, of course, a historical backdrop that formed the foundation of experience for Southerners in 1860. More than 4 million enslaved human beings lived in the south, and they touched every aspect of the region’s social, political, and economic life. Slaves did not just work on plantations. In cities such as Charleston, they cleaned the streets, toiled as bricklayers, carpenters, blacksmiths, bakers, and laborers. They worked as dockhands and stevedores, grew and sold produce, purchased goods and carted them back to their masters’ homes where they cooked the meals, cleaned, raised the children, and tended to the daily chores. “Charleston looks more like a Negro country than a country settled by white people,” a visitor remarked.

Fear of a slave rebellion was palpable. The establishment of a black republic in Haiti and the insurrections, threatened and real, of Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey, and Nat Turner stoked the fires. John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry sent shock waves through the south. Throughout the decades leading up to 1860, slavery was a burning national issue, and political battles raged over the admission of new states as slave or free. Compromises were struck – the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850 – but the controversy could not be laid to rest.

The South felt increasingly beleaguered as the North increased its criticism of slavery. Abolitionist societies sprang up, Northern publications demanded the immediate end of slavery, politicians waxed shrill about the immorality of human bondage, and overseas, the British parliament terminated slavery in the British West Indies. A prominent historian accurately noted that “by the late 1850’s most white Southerners viewed themselves as prisoners in their own country, condemned by what they saw as a hysterical abolition movement.”

As Southerners became increasingly isolated, they reacted by becoming more strident in defending slavery. The institution was not just a necessary evil: it was a positive good, a practical and moral necessity. Controlling the slave population was a matter of concern for all Whites, whether they owned slaves or not. Curfews governed the movement of slaves at night, and vigilante committees patrolled the roads, dispensing summary justice to wayward slaves and whites suspected of harboring abolitionist views. Laws were passed against the dissemination of abolitionist literature, and the South increasingly resembled a police state. A prominent Charleston lawyer described the city’s citizens as living under a “reign of terror.”

WHAT THE CHURCHES WERE SAYING

With that backdrop, let’s take our trip back in time to hear what Southerners were hearing. What were they being told by their pastors, by their politicians, and their community leaders about slavery, Lincoln, and secession?

Churches were the center of social and intellectual life in the south. That was where people congregated, where they learned about the world and their place in it, and where they received moral guidance. The clergy comprised the community’s cultural leaders and educators and carried tremendous influence with slaveholders and non-slaveholders alike. What were Southern pastors, preachers, and religious leaders telling their flock?

Southern clergy defended the morality of slavery through an elaborate scriptural defense built on the infallibility of the Bible, which they held up as the universal and objective standard for moral issues. Religious messages from pulpit and from a growing religious press accounted in large part for the extreme, uncompromising, ideological atmosphere of the time.

As Northern opposition to slavery grew, the three major protestant churches split into northern and southern factions. The Presbyterians divided in1837, the Methodists in 1844, and the Baptists in 1845. The segregation of the clergy into Northern and Southern camps was profound. It spelt an end to meaningful dialogue, leaving Southern preachers to talk to Southern audiences without contradiction.

What were their arguments? The Presbyterian theologian Robert Lewis Dabney reminded his fellow Southern clergymen that the Bible was the best way to explain slavery to the masses. “We must go before the nation with the Bible as the text, and ‘thus sayeth the lord’ as the answer,” he wrote. “We know that on the Bible argument the abolition party will be driven to unveil their true infidel tendencies. The Bible being bound to stand on our side, they have to come out and array themselves against the Bible.”

Reverend Furman of South Carolina insisted that the right to hold slaves was clearly sanctioned by the Holy Scriptures. He emphasized a practical side as well, warning that if Lincoln were elected, “every Negro in South Carolina and every other Southern state will be his own master; nay, more than that, will be the equal of every one of you. If you are tame enough to submit, abolition preachers will be at hand to consummate the marriage of your daughters to black husbands.”

A fellow reverend from Virginia agreed that on no other subject “are [the Bible’s] instructions more explicit, or their salutary tendency and influence more thoroughly tested and corroborated by experience than on the subject of slavery.” The Methodist Episcopal Church, South, asserted that slavery “has received the sanction of Jehova.” As a South Carolina Presbyterian concluded: “If the scriptures do not justify slavery, I know not what they do justify.”

The Biblical argument started with Noah’s curse on Ham, the father of Canaan, which was used to demonstrate that God had ordained slavery and had expressly applied it to Blacks. Commonly cited were passages in Leviticus that authorized the buying, selling, holding and bequeathing of slaves as property. Methodist Samuel Dunwody from South Carolina documented that Abraham, Jacob, Isaac, and Job owned slaves, arguing that “some of the most eminent of the Old Testament saints were slave holders.” The Methodist Quarterly Review noted further that “the teachings of the new testament in regard to bodily servitude accord with the old.” While slavery was not expressly sanctioned in the New Testament, Southern clergymen argued that the absence of condemnation signified approval. They cited Paul’s return of a runaway slave to his master as Biblical authority for the Fugitive Slave Act, which required the return of runaway slaves.

As Pastor Dunwody of South Carolina summed up the case: “Thus, God, as he is infinitely wise, just and holy, never could authorize the practice of a moral evil. But god has authorized the practice of slavery, not only by the bare permission of his Providence, but the express provision of his word. Therefore, slavery is not a moral evil.” Since the Bible was the source for moral authority, the case was closed. “Man may err,” said the southern theologian James Thornwell, “but God can never lie.”

It was a corollary that to attack slavery was to attack the Bible and the word of God. If the Bible expressly ordained slave holding, to oppose the practice was a sin and an insult to God’s word. As the Baptist minister and author Thornton Stringfellow noted in his influential Biblical Defense of Slavery, “men from the north” demonstrated “palpable ignorance of the divine will.”

The Southern Presbyterian of S.C observed that there was a “religious character to the present struggle. Anti-slavery is essentially infidel. It wars upon the Bible, on the Church of Christ, on the truth of God, on the souls of men.” A Georgia preacher denounced abolitionists as “diametrically opposed to the letter and spirit of the Bible, and as subversive of all sound morality, as the worst ravings of infidelity.” The prominent South Carolina Presbyterian theologian James Henley Thornwell did not mince his words. “The parties in the conflict are not merely abolitionists and slaveholders. They are atheists, socialists, communists, red republicans, Jacobins on the one side, and friends of order and regulated freedom on the other. In one word, the world is the battleground – Christianity and Atheism the combatants; and the progress of humanity at stake.”

During the 1850’s, pro-slavery arguments from the pulpit became especially strident. A preacher in Richmond exalted slavery as “the most blessed and beautiful form of social government known; the only one that solves the problem, how rich and poor may dwell together; a beneficent patriarchate.” The Central Presbyterian affirmed that slavery was “a relation essential to the existence of civilized society.” By 1860, Southern preachers felt comfortable advising their parishioners that “both Christianity and Slavery are from heaven; both are blessings to humanity; both are to be perpetuated to the end of time.”

By 1860, Southern churches were denouncing the North as decadent and sinful because it had turned from God and rejected the Bible. Since the North was sinful and degenerate, went their reasoning, the South must purify itself by seceding. As a South Carolina preacher noted on the eve of secession, “We cannot coalesce with men whose society will eventually corrupt our own, and bring down upon us the awful doom which awaits them.” The consequence was a pointedly religious bent to rising Southern nationalism. As the Southern Presbyterian wrote, “It would be a glorious sight to see this Southern Confederacy of ours stepping forth amid the nations of the world animated with a Christian spirit, guided by Christian principles, administered by Christian men, and adhering faithfully to Christian precepts,” ie., the slavery of fellow human beings.

Shortly after Lincoln’s election, Presbyterian minister Benjamin Morgan Palmer, originally from Charleston, gave a sermon entitled, “The South Her Peril and Her Duty.” He announced that the election had brought to the forefront one issue – slavery – that required him to speak out. Slavery, he explained, was a question of morals and religion, and was now the central question in the crisis of the Union. The South, he went on, had a “providential trust to conserve and to perpetuate the institution of slavery as now existing.” The South was defined by slavery, he observed. “It has fashioned our modes of life, and determined all of our habits of thought and feeling, and molded the very type of our civilization.” Abolition, said Palmer, was “undeniably atheistic.” The South “defended the cause of God and religion,” and nothing “is now left but secession.” Some 90,000 copies of a pamphlet incorporating the sermon were distributed.

Preachers were prominent at ceremonies held as troops marched off to war. In Petersburg, Virginia for example, Methodist minister R. N. Sledd railed against Northerners, an “infidel and fanatical foe” who embodied “the barbarity of an Atilla more than the civilization of the 19th Century” and who showed “contempt for virtue and religion according to their savage purpose.” Northerners, he warned, wanted to “undermine the authority of my Bible. You go to contribute to the salvation of your country from such a curse,” he told the departing soldiers. “You go to aid in the glorious enterprise of rearing in our sunny south a temple to constitutional liberty and Bible Christianity. You go to fight for your people and for the cities of your God.”

WHAT THE POLITICIANS WERE SAYING

What were the South’s politicians saying? In late 1860 and early 1861, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Louisiana appointed commissioners to travel to the other slave states and persuade them to secede. The commissioners addressed state legislatures, conventions, made public addresses, and wrote letters. Their speeches were printed in newspapers and pamphlets. These contemporaneous documents make fascinating reading and have recently been collected in a book by the historian Charles Dew.

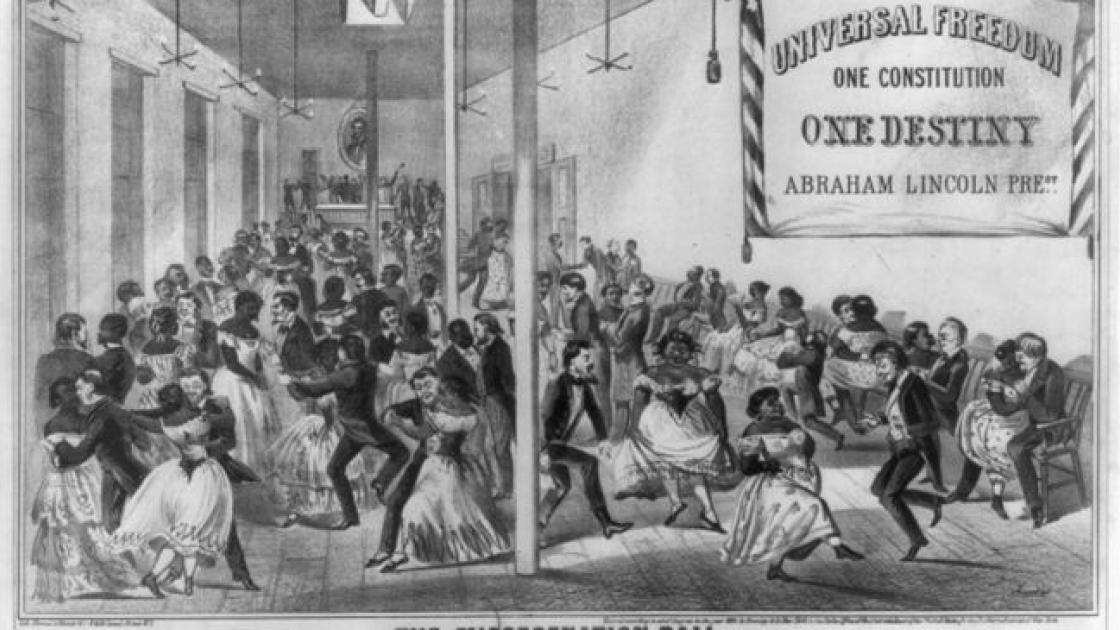

William Harris, Mississippi’s commissioner to Georgia, explained that Lincoln’s election had made the North more defiant than ever. “They have demanded, and now demand equality between the white and negro races, under our constitution; equality in representation, equality in right of suffrage, equality in the honors and emoluments of office, equality in the social circle, equality in the rights of matrimony,” he cautioned, adding that the new administration wanted “freedom to the slave, but eternal degradation for you and me.”

As Harris saw things, “Our fathers made this a government for the white man, rejecting the negro as an ignorant, inferior, barbarian race, incapable of self-government, and not, therefore, entitled to be associated with the white man upon terms of civil, political, or social equality.” Lincoln and his followers, he stated, aimed to “overturn and strike down this great feature of our union and to substitute in its stead their new theory of the universal equality of the black and white races.” For Harris, the choice was clear. Mississippi would “rather see the last of her race, men, women, and children, immolated in one common funeral pyre than see them subjugated to the degradation of civil, political and social equality with the negro race.” The Georgia legislature ordered the printing of a thousand copies of his speech.

Two days before South Carolina seceded, Judge Alexander Hamilton Handy, Mississippi’s commissioner to Maryland, warned that “the first act of the black republican party will be to exclude slavery from all the territories, from the District of Columbia, the arsenals and the forts, by the action of the general government. That would be a recognition that slavery is a sin, and confine the institution to its present limits. The moment that slavery is pronounced a moral evil – a sin – by the general government, that moment the safety of the rights of the south will be entirely gone.”

The next day, two commissioners addressed the North Carolina legislature and warned that Lincoln’s election meant “utter ruin and degradation” for the south. “The white children now born will be compelled to flee from the land of their birth, and from the slaves their parents have toiled to acquire as an inheritance for them, or to submit to the degradation of being reduced to an equality with them, and all its attendant horrors.”

Former South Carolina Congressman John McQueen was crystal clear about where things stood when he wrote to a group of Richmond civic leaders. Lincoln’s program was based upon the “single idea that the African is equal to the Anglo-Saxon, and with the purpose of placing our slaves on a position of equality with ourselves and our friends of every condition. We, of South Carolina, hope soon to greet you in a Southern Confederacy, where white men shall rule our destinies, and from which we may transmit to our posterity the rights, privileges, and honor left us by our ancestors.”

Typical of the commissioner letters is that written by Stephen Hale, an Alabama commissioner, to the Governor of Kentucky, in December 1860. Lincoln’s election, he observed, was “nothing less than an open declaration of war, for the triumph of this new theory of government destroys the property of the south, lays waste her fields, and inaugurates all the horrors of a San Domingo servile insurrection, consigning her citizens to assassinations and her wives and daughters to pollution and violation to gratify the lust of half-civilized Africans. The slave holder and non-slaveholder must ultimately share the same fate; all be degraded to a position of equality with free negroes, stand side by side with them at the polls, and fraternize in all the social relations of life, or else there will be an eternal war of races, desolating the land with blood, and utterly wasting all the resources of the country.”

What Southerner, Hale asked, “can without indignation and horror contemplate the triumph of negro equality, and see his own sons and daughters in the not distant future associating with free negroes upon terms of political and social equality?” Abolition would surely mean that “the two races would be continually pressing together,” and “amalgamation or the extermination of the one or the other would be inevitable.” Secession, argued Hale, was the only means by which the “heaven ordained superiority of the white over the black race” could be sustained. The abolition of slavery would either plunge the South into a race war or so stain the blood of the white race that it would be contaminated for all time.” Could southern men “submit to such degradation and ruin,” he asked, and responded to his own question, “God forbid that they should.”

Congressman Curry, another of Alabama’s commissioner’s, similarly warned his fellow Alabamans that “the subjugation of the south to an abolition dynasty would result in a saturnalia of blood.” Emancipation meant “the abhorrent degradation of social and political equality, the probability of a war of extermination between the races or the necessity of flying the country to avoid the association.” Typical also was the message from Henry Benning of Georgia – later one of General Lee’s most talented brigade commanders – to the Virginia legislature. “If things are allowed to go on as they are, it is certain that slavery is to be abolished,” he predicted. “By the time the north shall have attained the power, the black race will be in a large majority, and then we will have black governors, black legislatures, black juries, black everything. Is it to be supposed that the white race will stand for that? It is not a supposable case.”

What did Benning predict would happen? “War will break out everywhere like hidden fire from the earth. We will be overpowered and our men will be compelled to wander like vagabonds all over the earth, and as for our women, the horrors of their state we cannot contemplate in imagination. We will be completely exterminated,” he announced, “and the land will be left in the possession of the blacks, and then it will go back to a wilderness and become another Africa or Saint Domingo.”

“Join the north and what will become of you” he asked. “They will hate you and your institutions as much as they do now, and treat you accordingly. Suppose they elevate Charles Sumner to the presidency? Suppose they elevate Frederick Douglas, your escaped slave, to the presidency? What would be your position in such an event? I say give me pestilence and famine sooner than that.”

In sum, the commissioners described one apocalyptic vision after another – emancipation, race war, miscegenation. The collapse of white supremacy would be so cataclysmic that no self-respecting Southerner could fail to rally to the secessionist cause, they argued. Secession was necessary to preserve the purity and survival of the white race. This was the unvarnished, near universal message of southern political leaders to their constituencies.

WHAT COMMUNITY LEADERS WERE SAYING

Southerners heard the identical message from their community leaders. In the fall of 1860, John Townsend, owner of a cotton plantation on Edisto Island, authored a pamphlet delineating the consequences of Lincoln’s elevation to presidency. The abolition of slavery would be inevitable, he warned, which would mean “the annihilation and end of all Negro labor (agricultural especially) over the whole South. It means a loss to the planters of the South of, at least, FOUR BILLION dollars, by having this labor taken from them; and a loss, in addition, of FIVE BILLION dollars more, in lands, mills, machinery, and other great interests, which will be rendered valueless by the want of slave labor to cultivate the lands, and the loss of the crops which give to those interests life and prosperity.”

More to the point, he noted, abolition meant “the turning loose upon society, without the salutary restraints to which they are now accustomed, more than four millions of a very poor and ignorant population, to ramble in idleness over the country until their wants should drive most of them, first to petty thefts, and afterwards to the bolder crimes of robbery and murder.” The planter and his family would “not only to be reduced to poverty and want, by the robbery of his property, but to complete the refinement of the indignity, they are to be degraded to the level of an inferior race, be jostled by them in their paths, and intruded upon, and insulted over by rude and vulgar upstarts. Who can describe the loathsomeness of such an intercourse;—the constrained intercourse between refinement reduced to poverty, and swaggering vulgarity suddenly elevated to a position which it is not prepared for?”

Non-slaveholders, he predicted, were also in danger. “It will be to the non-slaveholder, equally with the largest slaveholder, the obliteration of caste and the deprivation of important privileges,” he cautioned. “The color of the white man is now, in the South, a title of nobility in his relations as to the negro,” he reminded his readers. “In the Southern slaveholding States, where menial and degrading offices are turned over to be per formed exclusively by the Negro slave, the status and color of the black race becomes the badge of inferiority, and the poorest non-slaveholder may rejoice with the richest of his brethren of the white race, in the distinction of his color. He may be poor, it is true; but there is no point upon which he is so justly proud and sensitive as his privilege of caste; and there is nothing which he would resent with more fierce indignation than the attempt of the Abolitionist to emancipate the slaves and elevate the Negroes to an equality with himself and his family.”