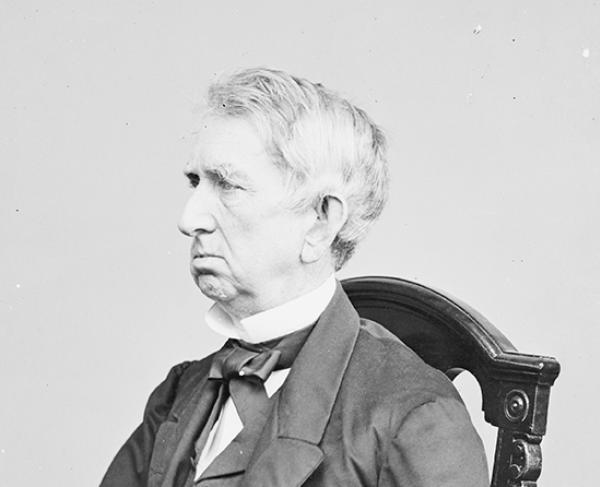

William H. Seward

William Henry Seward was a young New York lawyer traveling through Rochester in 1824 when he was involved in a momentous stage-coach accident. The accident itself was minor, but it would have continent-altering ramifications, for one of the pedestrians that came to help was a local newspaperman and aspiring politician named Thurlow Weed.

Seward was born in 1801 to a large and well-to-do family in Florida, New York. In his early years one of his playing companions was a boy named Zeno, a young slave from a neighboring household. One day Zeno told Seward that he had been brutally beaten. The next day he tried to run, was caught, and was forced to wear an iron yoke around his neck. He soon broke the yoke and made good his escape; Seward never saw him again. Writing later, he remembered that such events “determined me, at that early age, to become an abolitionist.”

From the age of 12, Seward attended the S.S. Seward Institute, named for his father, before traveling twenty miles from home to Union College. After graduating with honors he joined the New York state bar in 1821. For the next three years, he split his time between practicing law and the courtship of a woman named Frances Miller. In 1824 they were married, and Seward moved to her hometown of Auburn, New York to open a law partnership with her father.

The stage-coach accident was the first step in Seward’s political career. Thurlow Weed struck up a friendship with the young lawyer based on their loathing for Masonic influences in politics and their relationship grew during Seward’s frequent business visits to Rochester. After being elected to the New York state legislature, Weed became something of a mentor to Seward, and on the strength of his counsel, Seward was elected to the state senate in 1831.

Seward was outgoing, intelligent, and eloquent, and his star soon began to rise in New York politics. In 1834 he shifted his alignment from the Anti-Masonic faction to the newly formed Whig party but was narrowly defeated in a gubernatorial bid by Democratic incumbent William Marcy. In the meantime, Thurlow Weed was building the Evening Journal into the most circulated political newspaper in the country. He threw the weight of his presses behind Seward and in 1838 the candidate secured the governorship. Fourteen years after their chance meeting beside a fouled stage-coach, the young companions had grown into the most powerful political duo in the state of New York.

Seward served as governor for two two-year terms, primarily pursuing prison reform, universal education, and internal improvements. Seward demurred from running in the 1842 election and went back to Auburn to practice law. His most notable case came in 1846 when he took up the defense of William Freeman, a mentally ill black man accused of murdering four people. The case, with overtones of racial tension, madness, and extreme violence, drew the attention of the entire nation. In a powerful argument, Seward quoted one of Freeman’s family members:

They have made William Freeman what he is, a brute beast; they don’t make anything else of any of our people but brute beasts; but when we violate their laws, then they want to punish us as if we were men.

Freeman was found guilty but Seward won a stay of execution. He then successfully appealed the case to the New York Supreme Court, which ordered a new trial. While awaiting the new court date Freeman died of tuberculosis. In view of the circumstances, even such a tragic end was an almost unbelievable victory, one which further affirmed Seward’s strong progressive beliefs.

In 1849 he was elected to the United States Senate. The national conversation at the time was convulsed by the enmity between pro and anti-slavery factions. The Compromise of 1850, which admitted California as a free state in exchange for strengthening the Fugitive Slave Act, further aggravated these tensions. Seward strongly opposed the compromise because it would compel northern citizens to return escaped slaves or face imprisonment. Before its passage he made a speech on the Senate floor in which he envisioned:

countless generations…rising up and passing in dim and shadowy review before us; and a voice comes forth from their serried ranks, saying: ‘Waste your treasures and your armies, if you will; raze your fortifications to the ground; sink your navies into the sea; transmit to us even a dishonored name, if you must; but the soil you hold in trust for us--give it to us free. You found it free, and conquered it to extend a better and surer freedom over it. Whatever choice you have made for yourselves, let us have no partial freedom; let us all be free; let the reversion of your broad domain descend to us unencumbered, and free from the calamities and from the sorrows of human bondage.’

Meanwhile, his wife Frances established their Auburn home as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Many runaway slaves, including Harriet Tubman, received money and assistance from the Seward family on their journey to freedom.

By 1859 the Whig party had splintered. Seward and Weed joined the Republican party and Seward entered the presidential primary. As the prohibitive favorite, Seward took an extended trip overseas on Weed’s advice in order to avoid the possibility of an unnecessary blunder before the general election. Instead, he returned to find the dark horse candidate, Abraham Lincoln, making enormous gains. Additionally, Weed’s heavy-handed sponsorship of his old friend was repelling key delegates. Seward lost the primary. Gamely, he went on the stump for Lincoln and eventually played a critical role in securing the Illinois Republican’s victory.

Seward’s support earned him the cabinet post of Secretary of State in Lincoln’s fledgling administration and a position of unique friendship with the struggling president. One day Seward walked into the Oval Office to find Lincoln polishing his boots. Seward pointed out that men of their high office “do not blacken our own boots.” Lincoln looked up with a smile and asked, “Then whose boots do you blacken, Mr. Secretary?”

There was little time for humor as the rumblings of an inevitable war began to shake the nation. Seward proposed provoking an international conflict to divert attention from domestic problems, but Lincoln refused. After the war began Seward devoted his time to preventing foreign powers from coming to the aid of the Confederacy.

His attempts came to a crisis point during the Trent Affair of 1862, in which an overzealous Union naval captain, Charles Wilkes, boarded a British ship and seized two Confederate envoys on a diplomatic mission. Britain felt that its neutrality had been violated and there were many in the United States who felt that Britain’s neutrality could use some violating. Seward ordered the release of the diplomats and renounced the captain’s deeds, but did not apologize. Throughout the scandal, which took place from August of 1861 through January of 1862, Seward charted a skillful political course that bolstered the United States’ reputation for lawfulness while impressing upon the British, and by extension the French, government that the young nation would strongly resist foreign intervention.

On the basis of agreements initially proposed during the Trent Affair, Seward also orchestrated the Lyons-Seward Treaty of 1862. By this treaty, the United States and Britain policed each other’s trans-Atlantic shipping for human contraband cargo. This pact finally spelled the end of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Britain continued to push the boundaries of its professed neutrality in the conflict. Two warships, the C.S.S. Florida and the C.S.S. Alabama were secretly built in British shipyards and sent to the Confederacy. The protests of the American diplomatic corps, with Seward at its head, led to intense embarrassment in Britain. Their shipyards would no longer produce for the Confederate states, notably halting the delivery of two ironclads that would have likely proved greatly advantageous to the southern navy.

In April of 1865, Seward was involved in another stage-coach accident. He habitually rode outside of the carriage body in order to smoke cigars and in this instance was thrown clear and badly injured. He was recuperating in his bed when his friend Lincoln came with news of Grant’s final victory in Virginia. Francis Carpenter recalled the scene:

After words of sympathy and condolence, with a countenance beaming with joy and satisfaction, he entered upon an account of his visit to Richmond, and the glorious success of Grant, - throwing himself, in his almost boyish exultation, at full length across the bed, supporting his head upon one hand, and in this manner reciting the story of the collapse of the Rebellion.

Lincoln left soon afterward. Three days later he was assassinated at the Ford Theater. That same night one of John Wilkes Booth’s co-conspirators arrived on Seward’s doorstep, claiming to carry an urgent message from the doctor. Seward’s son Frederick repeatedly denied him entry, at which point the stranger, Lewis Paine, aimed a pistol at his head. In the words of Frederick:

And now, in swift succession, like the scenes of some hideous dream, came the bloody incidents of the night, – of the pistol missing fire, – of the struggle in the dimly lighted hall, between the armed man and the unarmed one, – of the blow which broke the pistol of the one, and fractured the skull of the other, – of the bursting in of the door, – of the mad rush of the assassin to the bedside, and his savage slashing, with a bowie knife, at the face and throat of the helpless Secretary, instantly reddening the white bandages with streams of blood, – of the screams of the daughter for help, – of the attempt of the invalid soldier nurse to drag the assailant from his victim, receiving sharp wounds himself in return, – of the noise made by the awaking household, inspiring the assassin with hasty impulse to escape, leaving his work done or undone, of his frantic rush down the stair, cutting and slashing at all whom he found in his way, wounding one in the face, and stabbing another in the back, – of his escape through the open doorway, – and his flight on horseback down the avenue.

Miraculously, Seward survived the attack and even made a full recovery. Frances made an unusual trip to Washington—she had been put off several years earlier by Mary Todd Lincoln’s assertion that she was “a dirty abolition sneak”—to look after her husband. The strain of Washington and fear for the safety of her family proved too much to bear. Frances died of a heart attack in June.

After taking the remaining family on a trip to the Caribbean, Seward returned to continue as Secretary of State under Andrew Johnson. He orchestrated the purchase of the Alaska territory in 1867, which became known as “Seward’s Icebox,” for two cents an acre. The decision was reviled at the time, but Seward later maintained that it was his greatest achievement even though it would “take the people a generation to find out.” The next year, he was instrumental in sustaining President Johnson throughout his impeachment.

After Johnson’s time in office Seward retired from public life. He struggled to find peace at home and embarked on a trip around the world from 1870 to 1871. He was in his home office in Auburn on October 10, 1872, when he began to have breathing problems. 48 years and six months after the stage-coach accident that had thrown him into the greatest drama in American history, William Henry Seward died. His last words were whispered to his children: “Love one another.”